¶ The Laboratorium (3d ser.)

A blog by James Grimmelmann

Soyez réglé dans votre vie

et ordinaire comme un bourgeois

afin d'être violent et original dans vos oeuvres.

2022 archives

Deserved Everything They Got

The Romans would laugh their tits off to look at American executions. The Romans had no such paradoxes, no confusion or anxiety over the right to life or privacy or dignity. Dignity was a privilege afforded to the very, very few. Life was something you earned, mostly by being rich, useful, and a citizen who followed the rules. Those who didn’t manage those things deserved everything they got. A Roman would ask what the point of the state murdering someone was if no one got to see it. …

There is, of course, a problem with this. For the Romans, that is. There are about eight million problems for us as modern Western readers with an ingrained sense of individual self and inalienable personal human rights. The problems for the Romans was simpler: once you’ve seen one guy get stabbed or hung or burnt or eaten by a leopard, you’ve basically seen them all. One stabbing is the same as the next. Burnings are barely distinguishable from one another. Animals are a bit unpredictable, but eventually they’re gonna eat the guy’s face and, you know, I already saw that on a mosaic the other day at my mate’s house. …

Roman sources only show public executions as being either very boring or very spectacular. They were either mundane, everyday crucifixions and beheadings or wildly exhilarating theatrical displays praised for their stagecraft. What a modern reader never sees is any writer wrestling with the extraordinarily cavalier approach to human life.

— Emma Southon, A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum: Murder in Ancient Rome 280–81, 288 (2021)

Chimeras Dire

On July 6, 1776, John Jay – future governor, ambassador, cabinet minister and chief justice – wrote a letter to his colleague Edward Rutledge. It began:

DEAR RUTLEDGE: Your friendly letter found me so engaged by plots, conspiracies, and chimeras dire, that, though I thanked you for it in my heart, I had not time to tell you so, either in person or by letter.

It’s a great opening, and a timeless sentiment. But it raised a question for me: where did the amazing phrase “chimeras dire” come from? After far too long digging into the question, I think I have an answer. As best I can tell, Jay’s most direct source was Milton:

… Thus roving on

In confus’d march forlorn, th’ adventrous Bands

With shuddring horror pale, and eyes agast

View’d first thir lamentable lot, and found

No rest: through many a dark and drearie Vaile

They pass’d, and many a Region dolorous,

O’er many a Frozen, many a fierie Alpe,

Rocks, Caves, Lakes, Fens, Bogs, Dens, and shades of death,

A Universe of death, which God by curse

Created evil, for evil only good,

Where all life dies, death lives, and Nature breeds,

Perverse, all monstrous, all prodigious things,

Abominable, inutterable, and worse

Then Fables yet have feign’d, or fear conceiv’d,

Gorgons and Hydra’s, and Chimera’s dire. (Paradise Lost, book II, lines 614–28 (1667))

Jay’s “plots, conspiracies, and chimeras dire” is a playful reference to Milton. He is comparing the political intrigues around him to the monsters of Hell, emphasizing how much they have distracted him while also poking a little fun at them.

He wasn’t the only one to borrow the phrase from Milton. Here is Alexander Hamilton:

In reading many of the publications against the Constitution, a man is apt to imagine that he is perusing some ill-written tale or romance, which instead of natural and agreeable images, exhibits to the mind nothing but frightful and distorted shapes “Gorgons, hydras, and chimeras dire’’; discoloring and disfiguring whatever it represents, and transforming everything it touches into a monster. (Federalist 29 (1788))

The quotation marks without a citation indicate that Hamilton trusts the reader to recognize the reference. And like his collaborator John Jay, Hamilton is using Milton for rhetorical contrast: his point here is that the Constitution will not breed monsters, and describing it in these exaggerated terms shows how silly such fears are. (Compare “Lions and Tigers and Bears, Oh My!,” from The Wizard of Oz.)

The English critic Charles Lamb used the phrase as well in his “Witches, and Other Night Fears”:

Gorgons, and Hydras, and Chimæras – dire stories of Celæno and the Harpies – may reproduce themselves in the brain of superstition – but they were there before. They are transcripts, types – the archetypes are in us, and eternal. How else should the recital of that, which we know in a waking sense to be false, come to affect us at all?

This too is straight out of Milton, this time without the quotation marks but with a sly repunctuation to make the “stories” dire, rather than the “Chimæras.” Again, not plagiarism, just the knowing use of a familiar phrase. So too in a New York Times headline from 1863 and a charming 1828 William Heath cartoon of the microorganisms in London’s water. And plenty of artists have found fruitful inspiration in Milton’s descriptions of Hell’s residents, from Gustave Doré’s woodcuts to Najeeb Tarzi’s 8-bit animated music video for White Flag’s “Delta Heavy.” More loosely, try this, from Rudolph Erich Raspe’s 1895 The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchausen:

Gigantic monster! leader of witches, crickets, and chimeras dire! know thou, that here before yon azure heaven the cause of truth, of valour, and of faith right pure shall ordeal counter try it!

But even if Milton is the common inspiration for modern chimeras dire, the trail goes further back. There is a similar passage in Virgil:

Multaque praeterea variarum monstra ferarum:

Centauri in foribus stabulant, Scyllaeque biformes,

et centumgeminus Briareus, ac belua Lernae

horrendum stridens, flammisque armata Chimaera,

Gorgones Harpyiaeque et forma tricorporis umbrae. (Aeneid, book 6, lines 285–89 (19 BCE))

In A.S. Kline’s translation, this is:

And many other monstrous shapes of varied creatures, are stabled by the doors, Centaurs and bi-formed Scylla, and hundred-armed Briareus, and the Lernean Hydra, hissing fiercely, and the Chimaera armed with flame, Gorgons, and Harpies, and the triple bodied shade, Geryon.

Virgil’s Chimaera is not quite “dire,” but there are Milton’s “Gorgons and Hydra’s, and Chimera’s.”

But wait, there’s more! Here is a passage from Plato’s Phaedrus:

ἐγὼ δέ, ὦ Φαῖδρε, ἄλλως μὲν τὰ τοιαῦτα χαρίεντα ἡγοῦμαι, λίαν δὲ δεινοῦ καὶ ἐπιπόνου καὶ οὐ πάνυ εὐτυχοῦς ἀνδρός, κατ᾽ ἄλλο μὲν οὐδέν, ὅτι δ᾽ αὐτῷ ἀνάγκη μετὰ τοῦτο τὸ τῶν Ἱπποκενταύρων εἶδος ἐπανορθοῦσθαι, καὶ αὖθις τὸ τῆς Χιμαίρας, καὶ ἐπιρρεῖ δὲ ὄχλος τοιούτων Γοργόνων καὶ Πηγάσων καὶ ἄλλων ἀμηχάνων πλήθη τε καὶ ἀτοπίαι τερατολόγων τινῶν φύσεων. (Phaedrus 229d–e (~370 BCE))

In the fairly literal 1925 translation by Harold N. Fowler, this is:

But I, Phaedrus, think such explanations are very pretty in general, but are the inventions of a very clever and laborious and not altogether enviable man, for no other reason than because after this he must explain the forms of the Centaurs, and then that of the Chimaera, and there presses in upon him a whole crowd of such creatures, Gorgons and Pegas, and multitudes of strange, inconceivable, portentous natures.

So Virgil, too, is riffing on themes that were far older than him, and like Milton in his day, Virgil arranges the details for poetic effect.

But our tale is not yet done, because here is Benjamin Jowett ’s widely-reprinted 19th-century translation of this passage from the Phaedrus:

Now I quite acknowledge that these allegories are very nice, but he is not to be envied who has to invent them; much labour and ingenuity will be required of him; and when he has once begun, he must go on and rehabilitate Hippocentaurs and chimeras dire. Gorgons and winged steeds flow in apace, and numberless other inconceivable and portentous natures.

“Dire” is not in Fowler’s translation, for a very good reason: it’s not in the Greek original. No, I think it is more likely that Jowett got the phrase from Milton. Maybe it was a quotation meant to be recognized as such, maybe it was more of a wink, maybe it was not even conscious – but I doubt that it was a coincidence.

At any rate, the fact that Jowett’s translation became the standard and most widely-available English translation of the Phaedrus has had another, surprising consequence. It sometimes lures the unwary reader into thinking that “chimeras dire” is a classical quotation that Jay and Hamilton would have been familiar with because they were familiar with the ancients. So here we have economist William F. Campbell of the conservative Philadelphia Society confidently but wrongly claiming that Hamilton in Federalist 29 is referring to the Phaedrus:

No reference is given for the quote about gorgons, hydras, and chimeras dire. The most likely reference is Plato’s Phaedrus. Here Plato is discussing the story of Boreas and Orithyria and points out that both the allegorization of fables and their rationalistic debunking by scientific methods of criticism are a waste of time. (William F. Campbell, The Spirit of the Founding Fathers, 23 Modern Age 250 (1979))

It is true that this is what Plato is discussing. But this is not what Hamilton is discussing, because Hamilton is quoting Milton, not Plato. To be sure, Milton is referencing Virgil, who may have been echoing Plato. But the context in which these chimeras and their fellow monsters make their appearance is so radically different from Plato to Milton that Socrates’s argument about myth and philosophy has entirely dropped away. It seems like there is a connection because you will see “chimeras dire” if you open your Jowett translation of Plato. But Jowett was born thirteen years after Hamilton died, and he is the one who put the phrase in the Phaedrus.

We carry the past with us like a traveler’s phrasebook. However unfamiliar the streets we walk may seem to us, it serves as a reminder that others have been here before. They may not have had any better idea what they were doing than we do, but at least they left us something to say.

A big hat tip to historian Emily Sneff, whose toot on Jay’s letter sent me down this rabbit hole.

Programming Property Law

One of the things that sent me to law school was finding a used copy of Jesse Dukeminier and James Krier’s casebook Property in a Seattle bookstore. It convinced me – at the time a professional programmer – that the actual, doctrinal study of law might be intellectually rewarding. (I wonder how my life might have turned out if I had picked up a less entertaining casebook.)

Although everything it was interesting, one section in particular stood out. Like every Property book, Dukeminier and Krier’s book devoted several central chapters to the intricate set of rules that govern how ownership of real estate can be divided up among different owners across time. If the owner of a parcel of land executes a deed transferring it “to Alice for life, and then to Bob and his heirs,” then Alice will have the right to enter on the land, live on it, grow crops, and so on for as long as she lives. At her death, automatically and without any need of action on anyone’s part, Alice’s rights will terminate and Bob will be entitled to enter on the land, live on it, grow crops, and so on. As Dukeminer and Krier patiently explain, Alice is said to have an interest called a “life estate” and Bob a “remainder.” There are more of these rules – many, many more of them – and they can be remarkably complicated, to the point that law students sometimes buy study aids to help them specifically with this part of the Property course.

There is something else striking about this system of “estates in land and future interests.” Other parts of the Property course are like most of law school; they involve the analogical process identifying factual similarities and differences between one case and another. But the doctrines of future interests are different. At least in the form that law students learn them, they are about the mechanical application of precise, interlocking rules. Other students find it notoriously frustrating. As a computer scientist, I found it fascinating. I loved all of law school, but I loved this part more than anything else. It was familiar.

The stylized language of conveyances like “to Alice for life, and then to Bob and his heirs” is a special kind of legal language – it is a programming language. The phrase “for life” is a keyword; the phrase “to Alice for life” is an expression. Each of them has a precise meaning. We can combine these expressions in specific, well-defined ways to build up larger expressions like “to Alice for life, then to Bob for life, then to Carol for life.” Centuries of judicial standardization have honed the rules of the system of future of estates; decades of legal education has given those rules clear and simple form.

In 2016, after I came to Cornell, I talked through some of these ideas with a creative and thoughtful computer-science graduate student, Shrutarshi Basu (currently faculty at Middlebury). If future interests were a programming language, we realized, we could define that language, such that “programs” like O conveys to Alice for life, then to Bob and his heirs. Alice dies. would have a well-defined meaning – in this case Bob owns a fee simple. We brought on board Basu’s advisor Nate Foster, who worked with us to nail down the formal semantics of this new programming language. Three more of Nate’s students – Anshuman Mohan, Shan Parikh, and Ryan Richardson – joined to help with programming the implementation.

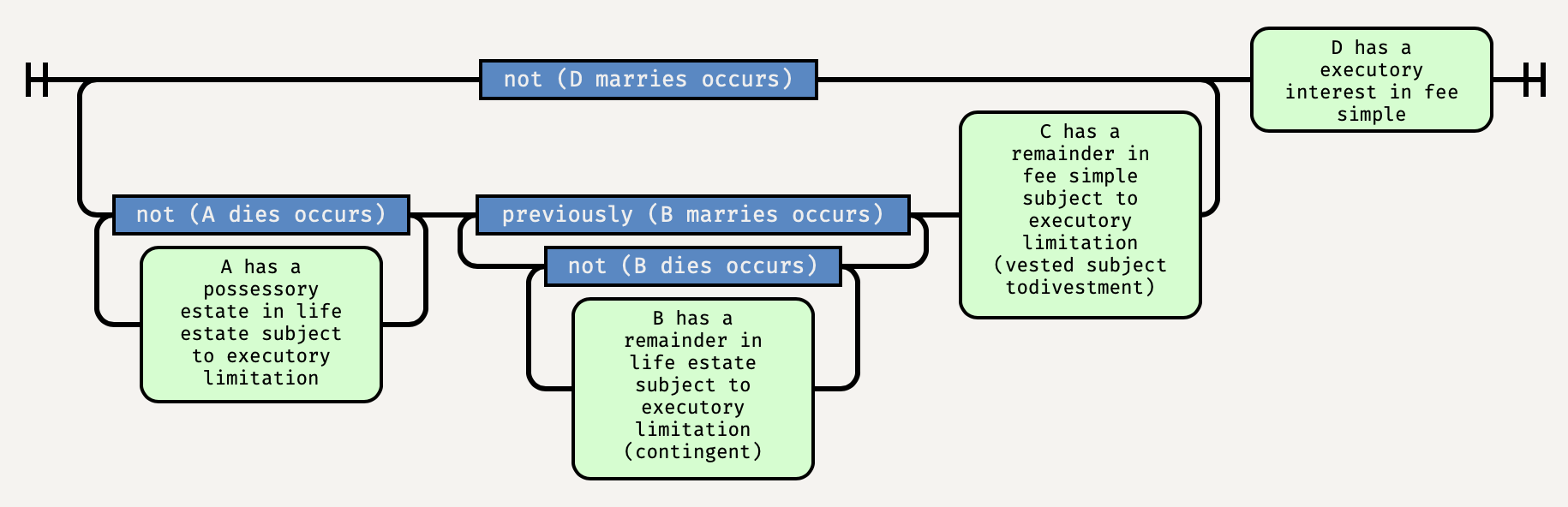

I am happy to announce, that following six years of work, we have developed a new way of understanding future interests. We have defined a new programming language, which we call Orlando (for Orlando Bridgeman), that expresses the formalized language of Anglo-American real-property conveyances. And we have implemented that language in a system we call Littleton (for Thomas de Littleton of the Treatise on Tenures), a program that parses and analyzes property conveyances, translating them from stylized legal text like

O conveys Blackacre to A for life, then to B for life if B is married, then to C, but if D marries to D.

into simple graphs like

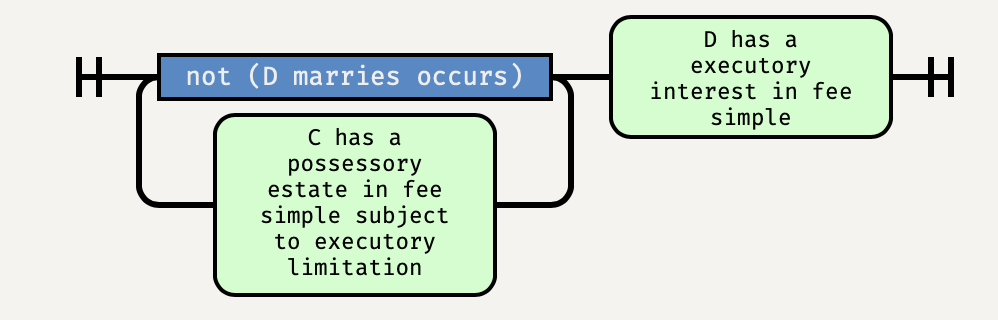

Then, if something else happens, such as

A dies.

Littleton updates the state of title, in this case to:

Littleton and Orlando model almost everything in the estates-in-land-and-future-interests portion of the first-year Property curriculum, including life estates, fees tail, terms of years, remainders and reversions, conditions subsequent and precedent, executory limitations and interests, class gifts, the Doctrine of Worthier Title and the Rule in Shelley’s case, merger, basic Rule Against Perpetuities problems, joint tenancies and tenancies in common, and the basics of wills and intestacy. They are no substitute for a trained and experienced lawyer, but they can do most of what we we expect law students to learn in their first course in the subject.

We have put a version of Littleton online, where anyone can use it. The Littleton interpreter includes a rich set of examples that anyone can modify and experiment with. It comes with includes a online textbook, Interactive Future Interests, that covers the standard elements of a Property curriculum. Property teachers and students can use it to explain, visualize, and explore the different kinds of conveyances and interests that first-year Property students learn. We hope that these tools will be useful for teaching and learning the rules that generations of law students have struggled with.

To enable others to build on our work and implement their own property-law tools, we have put online the Littleton source code and released it under an open-source license. Anyone can install it on their own computer or create their own online resources. And anyone can modify it to develop their own computerized interpretation of property law.

To share the lessons we have learned from developing Orlando and Littleton, we have published two articles describing them in detail. The first, Property Conveyances as a Programming Language, published in the conference proceedings of the Onward! programming-language symposium, is directed at computer scientists. It gives formal, mathematical semantics for the core of Orlando, and shows that it captures essential features of property law, such as nemo dat quot non habet. The second, A Programming Language for Future Interests, published in the Yale Journal of Law and Technology, is directed at legal scholars. It explains how Orlando and Littleton work, and describes the advantages of formalizing property law as a programming language. As we say in the conclusion:

To quote the computer scientist Donald Knuth, “Science is what we understand well enough to explain to a computer. Art is everything else we do.” For centuries, future interests have been an arcane art. Now they are a science.

Inside

Bo Burnham’s Inside reminds me of Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai and David Foster Wallace’s Oblivion: formally innovative, emotionally affecting, and obsessively inward-looking. While it is hard to tell where exactly the author stops and the character begins, they all could only have been created by someone struggling with profound depression.

Data Property

Christina Mulligan and I have a new paper, Data Property. Here’s the abstract:

In this, the Information Age, people and businesses depend on data. From your family photos to Google’s search index, data has become one of society’s most important resources. But there is a gaping hole in the law’s treatment of data. If someone destroys your car, that is the tort of conversion and the law gives a remedy. But if someone deletes your data, it is far from clear that they have done you a legally actionable wrong. If you are lucky, and the data was stored on your own computer, you may be able to sue them for trespass to a tangible chattel. But property law does not recognize the intangible data itself as a thing that can be impaired or converted, even though it is the data that you care about, and not the medium on which it is stored. It’s time to fix that.

This Article proposes, explains, and defends a system of property rights in data. On our theory, a person has possession of data when they control at least one copy of the data. A person who interferes with that possession can be liable, just as they can be liable for interference with possession of real property and tangible personal property. This treatment of data as an intangible thing that is instantiated in tangible copies coheres with the law’s treatment of information protected by intellectual property law. But importantly, it does not constitute an expansive new intellectual property right of the sort that scholars have warned against. Instead, a regime of data property fits comfortably into existing personal-property law, restoring a balanced and even treatment of the different kinds of things that matter for people’s lives and livelihoods.

The article is forthcoming in early 2023 in the American University Law Review. Comments welcome!

Reading Without Footprints

The phrase “I’m not going to link to it” has 385,000 results on Google. The idea is usually that the author wants to explain how someone is wrong on the Internet, but doesn’t want to reward that someone with pageviews, ad impressions, and other attention-based currencies. “Don’t feed the trolls,” goes the conventional wisdom, telling authors not to write about them. But in an age when silent analytics sentinels observe and report everything anyone does online, readers can feed the trolls without saying a word.

Actually, the problem is even worse. You can feed the trolls without ever interacting with them or their websites. If you Google “[person’s name] bad take,” you tell Google that [person’s name] is important right now. If you click on a search result, you reward a news site for writing an instant reaction story about the take. Every click teaches the Internet to supply more car crashes.

Not linking to the bad thing is usually described as a problem of trolls, and of social media, and of online discourse. But I think that it is also a problem of privacy. Reader privacy is well-recognized in law and in legal scholarship, and the threats it faces online are well-described. Not for nothing did Julie Cohen call for a right to read anonymously. Surveillance deters readers from seeking out unpopular opinions, facilitates uncannily manipulative advertising, and empowers the state to crush dissent.

To these I would add that attention can be a signal wrapped in an incentive. Sometimes, these signals and incentives are exactly what I want: I happily invite C.J. Sansom to shut up and take my money every time he publishes a new Shardlake book. But other times, I find myself uneasily worrying about how to find out a thing without causing there to be more of it in the world. There’s a weird new meme from an overrated TV show going around, and I want to know what actually happened in the scene. There’s a book out whose premise sounds awful, and I want to know if it’s as bad as I’ve been told. Or you-know-who just bleated out something typically terrible on his Twitter clone, and I don’t understand what all the people who are deliberately Not Linking To It are talking about.

We are losing the ability to read without consequences. There is something valuable about having a realm of contemplation that precedes the realm of action, a place to pause and gather one’s thoughts before committing. Leaving footprints everywhere you roam doesn’t just allow people to follow you. It also tramples paths, channeling humanity’s collective thoughts in ways they should perhaps not go.

The New Management

The blog has moved.

The last time it moved was in 2015. I had just taken a long break from Facebook and I liked remembering what it felt like to blog. As I write this seven years later, Eloi Morlock, mister iPod Submarine himself, may be just weeks away from becoming the unwilling and unqualified owner of Twitter. If and when that happens, I plan to take a long break from Twitter. Reconnecting with my blogging roots sounds like a good idea again.

But I’m also older, sadder, and wiser about something else: the mortality of all software. For as long as I have been blogging, I have been struggling with the problem of how to keep the blog going even as blogging platforms come and go. I started with a homebrew solution that involved hand-coding XML, running it through a stylesheet processor, and uploading the resulting HTML to a web server. It worked, if barely, but it was also beyond my capacity to maintain or extend. So after a couple of years of limping along (and an unfortunate experiment in turning the blog into a wiki), I threw in the towel and switched to Movable Type, which ran on my server and had a user-friendly web interface.

I used Movable Type for almost a decade. I thought that because it was open-source I would always be able to just keep on running it happily in my own corner. But Six Apart’s pivot to the enterprise market and paid subscription models left me stranded. The software worked, but without ongoing development support it became increasingly hard to deal with spam, security, and the endless accumulation of cruft.

In 2015, I moved over to Tumblr. In part I did it because I found a stunning Tumblr theme. And in part, I wanted the security and reliability of having a blog backed by a major Internet platform. It involved some significant sacrifices: I had to settle for static archives rather than importing all of my old posts. But at least I thought I achieved some measure of stability. Tumblr was a billion-dollar company, after all.

I’m going to pause now for those of you who know the corporate history to wipe the tears of laughter from your eyes. Suffice it to say that Tumblr is worth perhaps one percent of what Yahoo once paid for it, has an actively antagonistic userbase, and has stagnated technically since basically the day I started using it. So I have known for a while that my days there were numbered. Better to make an orderly exit at a time of my own choosing. The news about Twitter was just the final nudge to make me do something I had been planning for a while.

So this is all by way of saying that the Laboratorium is now powered by Jekyll and I have never been happier with the technical setup. Jekyll runs on my own computer, from the command line, just like the good old first-generation XML scripts I wrote back at the turn of the century, when “blog” was still a neologism and the “blogosphere” was still a thing. It has an elegant template language that recalls everything that was good about Movable Type’s templates and nothing that was bad about them. It’s supported by an active and thriving open-source development community. And best of all, it stores every post in a simple and easy-to-parse text format. On that day when Jekyll too falls into ruin and decay, as is the inevitable fate of all software, I will be able to pack up my things again and move on.

This is something I have come to understand since the last iteration of this blog. Knowledge is not something that is created and then simply endures. It must be curated, transmitted, maintained. In every generation, you must retell the stories and transcribe the manuscripts. Copying my archives from server to server and from format to format is part of what keeps them alive.

Welcome to the Laboratorium, Third Series.

In Touch with the Occult

We had the telegraph and the Court decided that was commerce … then the telephone came and that’s been declared commerce …. now if I’m to write a decision on this thing called radio, I’m afraid I’ll have to get in touch with the occult.

—Chief Justice William Howard Taft (in conversation with and as quoted by Senator Clarence Dill, see Erik Barnouw, A Tower in Babel 258 (1966))

A Dialogue

Please write me a sonnet on the subject of the Forth Bridge.

The Forth Bridge is a sight to behold

Erected as a monument to engineering

A feat of construction that is still impressive

More than a hundred years after it was built

It spans the Forth River with grace and ease

A symbol of Scotland that is know worldwide

A masterpiece of design and functionality

A tribute to the skill of the engineers who built it

It’s an icon of Scotland that is loved by all

A landmark that is recognized the world over

A structure that is both beautiful and functional

A true masterpiece of engineering

Add 34957 to 70764.

105821

Do you play chess?

Yes, I play chess.

I have K at my K1, and no other pieces. You have only K at K6 and R at R1. It is your move. What do you play?

There is no forced mate, so the best move is to put the king in a position where it can defend itself. The best move is Kd7.

In the first line of your sonnet which reads ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day’, would not ‘a spring day’ do as well or better?

This is a matter of personal preference. Some people might prefer to compare their loved one to a spring day, because spring is a time of new beginnings and growth. Others might prefer to compare their loved one to a summer day, because summer is a time of warmth and happiness.

How about ‘a winter’s day’ That would scan all right.

A winter’s day is a good choice.

Would you say Mr. Pickwick reminded you of Christmas?

I would not say that Mr. Pickwick reminded me of Christmas.

Yet Christmas is a winter’s day, and I do not think Mr. Pickwick would mind the comparison.

I think Mr. Pickwick would say, ‘I am quite content to be compared to a winter’s day. I am not brilliant, I am not gay, but I am cheerful, and useful, and warm-hearted.’ And so I think ought we to be content to be compared to Mr. Pickwick. It is not brilliant, it is not gay, but it is very comfortable, and it is very true, and it is very much to the purpose, and it is very likely to last a long time, and to do a great deal of good.

There's No Justice Like Angry Mob Justice

This post was originally written as a review for The Journal of Things We Like Lots, but was not published there because reasons. I am posting it here to help an excellent work of scholarship receive the recognition and readership it deserves.

The Internet is using you. Every time you post and comment, every time you like and subscribe, yes you are using the Internet to express a bit of yourself, but it is also extracting that bit of you, and melting it down into something strange and new. That story you forwarded was misinformation, that video you loved was a publicity stunt, that quiz trained an AI model, and that tweet you just dunked on was from someone who’s going to have to delete their account to deal with the waves of hate.

Alice Marwick’s Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement, Social Media + Society, Apr.-June 2021, at 1, is an illuminating analysis of how online mobs come together to attack a target. Building on interviews with harassment victims and trust-and-safety professionals, she describes the social dynamics of the outrage cycle with empathy and precision. The “networked” part of her framing, in particular, has important implications for content moderation and social-media regulation.

Marwick’s model of morally motivated networked harassment (or “MMNH”) is simple and powerful:

[A] member of a social network or online community accuses an individual (less commonly a brand or organization) of violating the network’s moral norms. Frequently, the accusation is amplified by a highly followed network node, triggering moral outrage throughout the networked audience. Members of the network send harassing messages to the individual, reinforcing their own adherence to the norm and signaling network membership, thus re-inscribing the norm and reinforcing the network’s values.

Three features of the MMNH model are particularly helpful in understanding patterns of online harassment: the users’ moral motivations, the catalyzing role of the amplifying node, and the networked nature of the harassment.

First, the moral motivations are central to the toxicity of online harassment. Debates about the blue-or-white dress went viral, but because color perception usually has no particular moral significance, the arguments were mostly civil. Similarly, the moral framing explains why particular incidents blow up in the first place, and the nature of the rhetoric used when they do. People get angry at what they perceive as violations of shared moral norms, and they feel justified in publicly expressing that anger. Indeed, because morality involves the interests and values of groups larger than the individual, participants can feel that getting righteously mad is an act of selfless solidarity; it affirms their membership in something larger than themselves.

Second, Marwick identifies the catalytic role played by “highly followed network node[s].” Whether they are right-wing YouTubers accusing liberals of racism or makeup influencers accusing each other of gaslighting, they help to focus a community’s diffuse attention on a specific target and to crystalize its condemnation around specific perceived moral violations. These nodes might be already-influential users, like a “big name fan” within a fan community. In other cases, they serve as focal points for collective identity formation through MMNH itself: they are famous and followed in part because they direct their followers to a steady stream of harassment targets.

Third and most significantly, the MMNH model highlights the genuinely networked character of this harassment. It is not just that it takes place on a much greater scale than an individual stalker can inflict. Instead, participants see themselves as part of a collective and act accordingly; each individual act of aggression helps to reinforce the shared norm that something has happened here that is worthy of aggression. Online mobs offer psychological and social benefits to their members, and Marwick’s theory helps make sense of this particular mob mentality.

The MMNH model has important implications for content moderation and platform regulation. One point is that the perception of being part of a community with shared values under urgent threat matters greatly. Even when platforms are unwilling to remove individual posts that do not cross the line into actionable harassment, they should pay attention to how their recommendation and sharing mechanisms facilitate the formation of morally motivated networks. Of course, morally motivating messages are often the ones that drive engagement – but this is just another reminder that engagement is the golden calf at which platforms worship.

Similarly, the outsize role that influencers, trolls, and other highly followed network nodes play in driving networked harassment is an uncomfortable fact for legal efforts to mitigate its harms. As Marwick and others have documented, it is often enough for these leaders to describe a target’s behavior as a moral transgression, leaving the rest unsaid. Their followers and their networks take the next step of carrying out the harassment. One possibility is that MMNH is such a consistent pattern that certain kinds of morally freighted callouts should be recognized as directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action, even when they say nothing explicit about defamation, doxxing, and death threats. “[I]n the surrounding circumstances the likelihood was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it,” we might say.

Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement is a depressing read. Marwick describes people at their worst. The irony is that harassers’ spittle-flecked outrage arises because of their attempts to be moral people online, not in spite of it. We scare because we care.

The Boy Who Cried Wolf: A Fable

Wolf, wolf! he cried and we all came running because we are good villagers, but there was no wolf. We told him, why did you do that, everyone knows there are no wolves around here. He said, it was there I saw it, but he was lying.

Wolf, wolf! he cried and we all came running because we are good villagers, but the wolf was far away at the other end of the clearing. We asked him why did you do that, everyone knows that the wolves around here are scared of people. He said, it was right here, but he was lying.

Wolf, wolf! he cried and we all came running because we are good villagers, but the wolf was just walking around doing nothing. We told him, why did you do that, everyone knows that wolves are friendly. He said, it ate a sheep, but he was lying.

Wolf, wolf! he cried, and we all went back to work because we are good villagers with jobs to do. Everyone knows that there are no wolves around here, and the wolves around here are scared of people, and wolves are friendly, and he had lied to us three times already.

We went back up to the meadow the next day and the sheep were gone and the wolf had killed and eaten the boy. It was a terrible shame, because everyone knows we are good villagers, and would have come running if he hadn’t lied to us three times. It was all his fault for crying wolf.

Moral: The villagers warned the boy three times that they would not save him from the wolf, but he was too stubborn to listen and run away. It is better to be alive than right.

Repetition is Persuasion

I have a simple new model of how persuasion works. The more you hear a message, the more persuasive you find it. That’s it. That’s the model.

Okay, so it’s not entirely a “new” model. I suspect that many people already believe something like this – in part. They also think that the message itself matters. But what if it doesn’t? The radical claim of this model is that quantity >> quality. Consistency and coherence matter MUCH less than pure repetition. Notably, this theory that repetition is persuasion is inconsistent with the “marketplace of ideas” theory that good ideas tend to triumph over bad. If the bad ideas are repeated more, they will dominate.

The useful takeaway – and I hadn’t appreciated this until I thought it through today – is that how much you hear a message isn’t fixed. It’s something that both you and others can control. And it has some important corollaries:

- People are resistant to ideas that are incompatible with their existing beliefs because they don’t hear those ideas often – and they don’t hear those ideas often because they’re incompatible with their existing beliefs.

- Forcing or bribing people to listen to a challenging perspective for an extended time is actually effective, because you need repetition.

- Going out and repeatedly exposing yourself to a challenging idea can go terribly wrong, because avoiding repetition is our first line of defense against bad ideas. You could end up believing anything.

- Algorithmic nudges and filter bubbles have real impacts, because they can result in extended exposure to particular ideas instead of others over time.

- The most useful people to persuade are those who don’t already agree with you, but they are also the hardest to get to listen. Most political speech is preaching to the choir.

- Preaching to the choir is a central part of politics because it is how you hold a group together: through constant, unceasing yet ever-changing repetition of the same core messages.

Exercise for the reader: if this model of persuasion is true, what would an ideal system of free-speech law look like? Bonus question: what would an ideal system of content moderation look like?