¶ The Laboratorium (3d ser.)

A blog by James Grimmelmann

Soyez réglé dans votre vie

et ordinaire comme un bourgeois

afin d'être violent et original dans vos oeuvres.

Times Out

The typical law-review article of 2015 looks a lot like the typical law-review article of 1965 or 1915: same arrangement of text and footnotes on the same size page, same general citation style, same this-that-and-the-other. But If there are differences, the article from fifty or a hundred years ago almost certainly looks better. It might feel a little musty, but it also feels inviting. You can imagine turning the pages with interest as you sit by the fireplace in a comfortable chair with a warm beverage. Its modern counterpart is bland and boring, dead on the page. Older law reviews were distinctive, too: you could tell Minnesota from Michigan from Marquette at a glance. Modern law reviews almost all look alike.

The culprit is the production process. A hundred years ago, a law review would have been mechanically typeset by a professional printer. That made the publication cycle slower and costlier, but it also meant that law reviews were designed with care. Desktop publishing democratized printing; law student with computers and Microsoft Word can produce camera-ready copy ready to send out for printing, and typically do. But since Word dominates the workflow, it it has become a kind of greatest common mediocrity in law-review design. Whatever an author submits will be hammered into the journal’s Word template and its standard predefined styles–styles that are often identical, and identically ugly, across many journals.

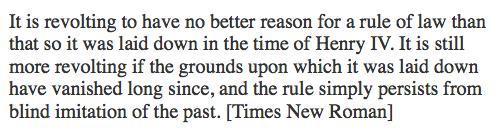

Typeface choice is a good example of the blandness of modern law reviews. Far and away the most common law-review typeface is the ubiquitous Times New Roman. It’s not a bad typeface, but it has become generic from massive overuse. To the modern eye, Times is the absence of design; it’s what you’re left with if you scrape every distinctive characteristic off your pages. For text intended to be unmemorable–memos from the associate dean, perhaps–Times is fine. In a law review, Times says, “Ignore me; I’m completely uninteresting. Go find something else to read.” This might be forgivable if Times were the perfect typeface for the law review page, but it isn’t. It’s a compact newspaper font, designed to save space in thin columns while preserving high legibility. Extended text–and 80-page articles are nothing if not extended–calls out for something with more grace, something easier on the eye in a lengthy reading session.

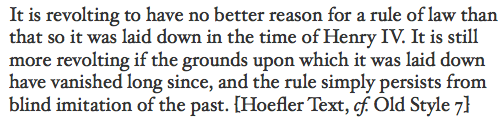

The best way to see what a poor choice Times New Roman is for a law review is to compare it to some better ones. At the other end of the spectrum–the good end–are Harvard and Yale. The Harvard Law Review is a model of consistency: it has stuck with the obscure and quirky Old Style 7 through thick and thin. The design dates to the 1870s, and it looks like it: the numerals and the italic have a late Victorian feel. The Harvard Law Review still speaks the same visual language it did when it was founded in 1887, which adds significantly to the feeling of gravitas and tradition its articles enjoy. You half expect to turn the page and come across something by Holmes, because what you’re reading is typeset in more or less the same way that The Path of the Law was. 1

The best way to see what a poor choice Times New Roman is for a law review is to compare it to some better ones. At the other end of the spectrum–the good end–are Harvard and Yale. The Harvard Law Review is a model of consistency: it has stuck with the obscure and quirky Old Style 7 through thick and thin. The design dates to the 1870s, and it looks like it: the numerals and the italic have a late Victorian feel. The Harvard Law Review still speaks the same visual language it did when it was founded in 1887, which adds significantly to the feeling of gravitas and tradition its articles enjoy. You half expect to turn the page and come across something by Holmes, because what you’re reading is typeset in more or less the same way that The Path of the Law was. 1

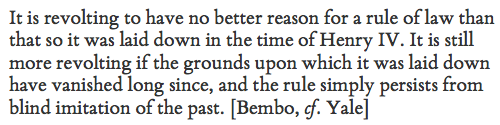

The Yale Law Journal’s design has varied more over the years (including an unfortunate run of Times). But its most recent redesign, based on the proprietary typeface Matthew Carter created for Yale University,2 is absolutely gorgeous. Carter’s work is meticulously based on the best of Renaissance font design, and his Yale typeface is classically elegant while being eminently readable. (For an example of its distinctive grace, zoom in on a lowercase ‘h’ and observe how the right leg bends inwards.) Yale paired it with Lucas de Groot’s fine TheSans to create one of the best looking law-review pages in the business.

The Yale Law Journal’s design has varied more over the years (including an unfortunate run of Times). But its most recent redesign, based on the proprietary typeface Matthew Carter created for Yale University,2 is absolutely gorgeous. Carter’s work is meticulously based on the best of Renaissance font design, and his Yale typeface is classically elegant while being eminently readable. (For an example of its distinctive grace, zoom in on a lowercase ‘h’ and observe how the right leg bends inwards.) Yale paired it with Lucas de Groot’s fine TheSans to create one of the best looking law-review pages in the business.

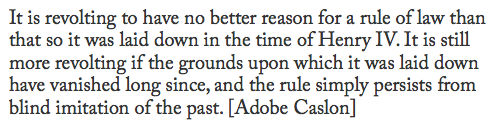

Two other standouts–the UCLA Law Review and the University of Pennsylvania Law Review–use variants of Caslon, a grand old standby of the typeface world. “When in doubt, use Caslon,” was conventional wisdom among printers, with good reason. Caslon has many of Times’s good qualities but few of the bad. It’s solid, unpretentious, easy to read for hours, and just plain comfortable. UCLA uses Carol Twombly’s Adobe Caslon, while Penn uses William Berkson’s Williams Caslon, both outstanding modern revivals. It’s interesting to compare the two pages to see how much of a difference small tweaks can make: UCLA’s is modern and unobtrusive, where Penn’s is classical and reserved. Both work well.

Two other standouts–the UCLA Law Review and the University of Pennsylvania Law Review–use variants of Caslon, a grand old standby of the typeface world. “When in doubt, use Caslon,” was conventional wisdom among printers, with good reason. Caslon has many of Times’s good qualities but few of the bad. It’s solid, unpretentious, easy to read for hours, and just plain comfortable. UCLA uses Carol Twombly’s Adobe Caslon, while Penn uses William Berkson’s Williams Caslon, both outstanding modern revivals. It’s interesting to compare the two pages to see how much of a difference small tweaks can make: UCLA’s is modern and unobtrusive, where Penn’s is classical and reserved. Both work well.

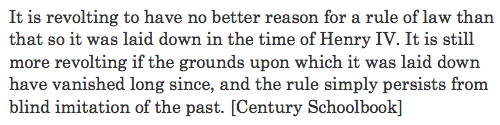

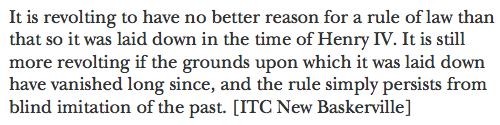

A few other typefaces show up with some regularity in law reviews. Century Schoolbook shows up here and there, e.g. in Minnesota and Chicago. It’s a fine choice: readable, clean, and familiar. Baskerville is another occasional choice; you see it, for example, in Iowa and Columbia. It too is a fine choice: crisp, professional, and serious. Both have excellent pedigrees in legal writing: Century Schoolbook is used for Supreme Court briefs and opinions, and Baskerville has been used for governmental publications since Ben Franklin fell in love with it.

A few other typefaces show up with some regularity in law reviews. Century Schoolbook shows up here and there, e.g. in Minnesota and Chicago. It’s a fine choice: readable, clean, and familiar. Baskerville is another occasional choice; you see it, for example, in Iowa and Columbia. It too is a fine choice: crisp, professional, and serious. Both have excellent pedigrees in legal writing: Century Schoolbook is used for Supreme Court briefs and opinions, and Baskerville has been used for governmental publications since Ben Franklin fell in love with it.

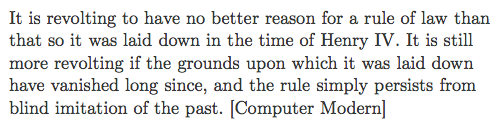

Also worthy of mention is Case Western’s use of Donald Knuth’s Computer Modern. There’s a meaningful connection between the face and the place: Knuth is a Case alum, though from the college rather than the law school. He’s one of the modern giants of computer science, and he created TeX, a landmark in computer typesetting. Computer Modern was his stab at a typeface to go with TeX. But Knuth is a better programmer than type designer, and Computer Modern is unattractive and hard on the eyes. But because it’s the default for TeX, it’s become the Times of technical papers. It’s not what I would have chosen, but it is distinctive, which is to say, at least it’s not Times.

Also worthy of mention is Case Western’s use of Donald Knuth’s Computer Modern. There’s a meaningful connection between the face and the place: Knuth is a Case alum, though from the college rather than the law school. He’s one of the modern giants of computer science, and he created TeX, a landmark in computer typesetting. Computer Modern was his stab at a typeface to go with TeX. But Knuth is a better programmer than type designer, and Computer Modern is unattractive and hard on the eyes. But because it’s the default for TeX, it’s become the Times of technical papers. It’s not what I would have chosen, but it is distinctive, which is to say, at least it’s not Times.

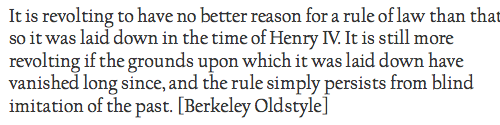

The great missed opportunity of law review font choice is that the California Law Review uses Times, rather than Berkeley Oldstyle, the typeface the great Frederic Goudy designed specifically for U.C. Berkeley. Not only is it a pleasing typeface, but its details make it as Californian as the Berkeley hills. (Look at the gentle curve on the upper arm of the lower-case ‘k’, for example.) Making the choice even more inexplicable, the university itself offers a digital version of Goudy’s design for download under the name “UC Berkeley Oldstyle.”

The great missed opportunity of law review font choice is that the California Law Review uses Times, rather than Berkeley Oldstyle, the typeface the great Frederic Goudy designed specifically for U.C. Berkeley. Not only is it a pleasing typeface, but its details make it as Californian as the Berkeley hills. (Look at the gentle curve on the upper arm of the lower-case ‘k’, for example.) Making the choice even more inexplicable, the university itself offers a digital version of Goudy’s design for download under the name “UC Berkeley Oldstyle.”

There are good reasons and bad reasons to pick a typeface for a law review. Licensing is a serious concern, and so is the logistical challenge of making sure that every editor’s computer has the appropriate fonts. But widely-used software frequently comes bundled with good fonts: if you have Adobe Reader on your computer, for example, you already have Robert Slimbach’s runaway hit Minion. And there are also freely available typefaces that are much better than Times, like Matthew Carter’s Charter.

There are good reasons and bad reasons to pick a typeface for a law review. Licensing is a serious concern, and so is the logistical challenge of making sure that every editor’s computer has the appropriate fonts. But widely-used software frequently comes bundled with good fonts: if you have Adobe Reader on your computer, for example, you already have Robert Slimbach’s runaway hit Minion. And there are also freely available typefaces that are much better than Times, like Matthew Carter’s Charter.

Law review editorial boards: if you want to up your typographic game, choosing a better typeface is a good place to start. Where by “better,” I mean “anything but Times.”

Law review editorial boards: if you want to up your typographic game, choosing a better typeface is a good place to start. Where by “better,” I mean “anything but Times.”

First in an occasional series on typography and legal academic writing.

On its website, Harvard uses Hoefler Text, which is a decent enough match for Old Style 7, comes preinstalled on Macs, and has advanced features like ligatures, ornaments, and bold. That’s how serious Harvard is about tradition: Old Style 7 doesn’t have bold, and neither does the Harvard Law Review. ↩︎

You can’t get the fonts unless you’re a Yale affiliate, and even then you’re only allowed to use them for University purposes. But commercially available fonts that capture some of the same flavor include Bembo, Dante, and Galliard (also a Carter design). ↩︎