¶ The Laboratorium (3d ser.)

A blog by James Grimmelmann

Soyez réglé dans votre vie

et ordinaire comme un bourgeois

afin d'être violent et original dans vos oeuvres.

Small Caps, Big Problem

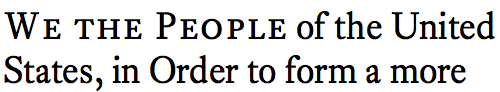

The second-most grievous sin of modern law-review typography is its casual disdain for proper small caps. Real small caps are created by a font designer to blend harmoniously with the rest of the letters. This is what they look like:1

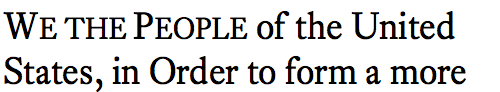

Fake small caps are created by a word processor by taking full-size capital letters and scaling them down. This is what they look like:

Fake small caps are created by a word processor by taking full-size capital letters and scaling them down. This is what they look like:  The differences are apparent, and so is the reason why. As a rule, font designers are better at typography than word processors. There are at least three things wrong with fake small caps:

The differences are apparent, and so is the reason why. As a rule, font designers are better at typography than word processors. There are at least three things wrong with fake small caps:

-

Fake small caps are too tall. Real small caps are closer to the typical height of lower-case letters, so they look better in mixed text.

-

Fake small caps are too light. Scaling down full-size letters produces thinner strokes. Real small caps have strokes that are consistent with the rest of the letters in a font. They look more solid on the page and they blend in better.

-

Fake small caps are too closely spaced. Upper-case letters resemble each other more than lower-case letters do, and they need to be spaced slightly further apart to make it easier for the eye to tell them apart.

Using real small caps is harder, but worth it. Sometimes, they come as a separate font file: in addition to Holmes Roman and Holmes Italic, you get Holmes Small Caps. Then, whenever you need to use small caps, you switch to the Small Caps font variant and there they are. This is how I typeset my casebook (sample chapter here), for example. I use Matthew Carter’s Miller and I switch between Miller Text Roman and Miller Text Roman SC as needed.

In other cases, the small-caps come packaged into the same font file as the regular letters. (This is how the OpenType font format standard works.) In theory, when you click the “small caps” command in your word processor, it switches to the right letters. In practice, your word processor ignores the real small caps in the file and makes its own ersatz small caps. For Microsoft Word, this is just par for the course. For Apple Pages, it’s especially frustrating because OS X is usually quite good about font technology. There are word processors that get this right, like Mellel, and sophisticated design programs like Indesign and Quark XPress handle real small caps, but none of these are great for a typical law review or legal scholar’s workflow.

The great irony here is that the Bluebook requires extensive use of small caps for book titles and authors and for journal names. The result is that the typical law-review page contains citations that the typical law review cannot typeset properly. Bad small caps are everywhere. Harvard and Yale have real small caps in the web versions of their articles but fake small caps in their PDFs. UCLA uses real small caps in its tables of contents but fake small caps in footnotes. Most law reviews don’t even try. It’s all the more striking to see the occasional law review that gets them right. The New York Law School Law Review, for example, uses them consistently and well in its PDFs. (Example here).

Law reviews that are looking to look better should start by choosing a better font than Times New Roman. And the very next thing they should do is use real small caps.

Second in an occasional series on typography and legal academic writing.

The typeface in the samples is Equity. Matthew Butterick designed it specifically for legal writing. He also has a charming rant against fake small caps. ↩︎