¶ The Laboratorium (3d ser.)

A blog by James Grimmelmann

Soyez réglé dans votre vie

et ordinaire comme un bourgeois

afin d'être violent et original dans vos oeuvres.

Posts about my own scholarship

Information Property

I am pleased to announce the public release of my freely available intellectual property textbook, Information Property. I have been working it since 2012. In that time, it has evolved from a collection of supplementary problems, to a coursepack, to a casebook, to a textbook. The result reflects how I think an IP survey course should be taught, because it is how I teach my own IP survey course. Here are a few highlights of what I have done, and why:

First, this is a textbook, not a casebook. Although it contains a few edited cases, most of it consists of my own explantions of IP doctrines and how they fit together. The point is to put in one place everything that a beginning IP student should know, clearly explained, and vividly illustrated. It contains hundreds of images: patent drawings, copyright works-in-suit, infringing products, and much much more.

Second, the book presents a systematic exposition of IP concepts. I have broken every IP field down into the same seven basic topics: subject matter, ownership, procedures, similarity, prohibited conduct, secondary liability, and defenses. It brings out the ways in which different fields are alike, and the ways in which they diverge. I find that this approach helps enormously in bringing order to what can seem like a riotous diversity of forms of IP.

Third, the book has unusually broad coverage of IP fields. In addition to the standard topics (patent, copyright, trademark, and sometimes trade secret), it also covers undeveloped ideas, false advertising, geographic indications, right of publicity, design patent—and a unique chapter on trademark-like issues in identifier registries.

Fourth, the book is freely available. I have released it under a Creative Commons Attribution license, and it is available from my website as a free PDF download. In addition, I sell at-cost paperback (black-and-white) and hardbound (full-color) versions through Lulu.

I am grateful to the many students and colleagues who have read previous versions of Information Property and given me useful suggestions on how to improve future ones. I plan to revise and extend it in the years to come, and your comments are warmly welcomed.

Generative Misinterpretation

I have a new article draft, Generative Misinterpretation, with Ben Sobel and David Stein, forthcoming in the Harvard Journal on Legislation. We argue against recent proposals to use LLMs in the judicial process. We combine an empirical critique, showing that experimental results in using LLMs to perform interpretation are brittle and arbitrary, with a jurisprudential critique, explaining why commonly offered justifications for using LLMs don’t work in the context of judging. Here is the abstract:

In a series of provocative experiments, a loose group of scholars, lawyers, and judges has endorsed generative interpretation: asking large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and Claude to resolve interpretive issues from actual cases. With varying degrees of confidence, they argue that LLMs are (or will soon be) able to assist—–or even replace—–judges in performing interpretive tasks like determining the meaning of a term in a contract or statute. A few go even further and argue for using LLMs to decide entire cases and to generate opinions supporting those decisions.

We respectfully dissent. In this Article, we show that LLMs are not yet fit for purpose for use in judicial chambers. Generative interpretation, like all empirical methods, must bridge two gaps to be useful and legitimate. The first is a reliability gap: are its methods consistent and reproducible enough to be trusted in high-stakes, real-world settings? Unfortunately, as we show, LLM proponents’ experimental results are brittle and frequently arbitrary. The second is an epistemic gap: do these methods measure what they purport to? Here, LLM proponents have pointed to (1) LLMs’ training processes on large datasets, (2) empirical measures of LLM outputs, (3) the rhetorical persuasiveness of those outputs, and (4) the assumed predictability of algorithmic methods. We show, however, that all of these justifications rest on unstated and faulty premises about the nature of LLMs and the nature of judging.

The superficial fluency of LLM-generated text conceals fundamental gaps between what these models are currently capable of and what legal interpretation requires to be methodologically and socially legitimate. Put simply, any human or computer can put words on a page, but it takes something more to turn those words into a legitimate act of legal interpretation. LLM proponents do not yet have a plausible story of what that “something more” comprises.

Comments welcome!

Listeners' Choices Online

I have posted a new draft essay, Listeners’ Choices Online. It is a sequel to my 2017 essay Listeners’ Choices, and like that piece it was written for a symposium on listeners’ interests. This one was hosted by the Southern California Law Review in November, and the final version will come out in the SCLR later this year. Here is the abstract:

The most useful way to think about online speech intermediaries is structurally: a platform’s First Amendment treatment should depend on the patterns of speaker-listener connections that it enables. For any given type of platform, the ideal regulatory regime is the one that gives listeners the most effective control over the speech that they receive.

In particular, we should distinguish four distinct functions that intermediaries can play. Broadcast, such as radio and television, transmits speech from one speaker to a large and undifferentiated group of listeners, who receive the speech automatically. Delivery, such as telephone, email, and broadband Internet, transmits speech from a single speaker to a single listener of the speaker’s choosing. Hosting, such as YouTube and Medium, allows an individual speaker to make their speech available to any listeners who seek it out. And selection, including search engines and feed recommendation algorithms, gives listeners suggestions about speech they might want to receive. Broadcast is relevant mostly as a (poor) historical analogue, but delivery, hosting, and selection are all fundamental on the Internet.

On the one hand, delivery and hosting intermediaries can sometimes be subject to access rules designed to give speakers the ability to use their platforms to reach listeners, because doing so gives listeners more choices among speech. On the other hand, access rules are somewhere between counterproductive and nonsensical when applied to selection intermediaries, because listeners rely on them precisely to make distinctions among competing speakers. Because speakers can use delivery media to target unwilling listeners, they can be subject to filtering rules designed to allow listeners to avoid unwanted speech. Hosting media, however mostly do not face the same problem, because listeners are already able to decide which content to request. Selection media, for their part, are what enable listeners to make these filtering decisions about speech for themselves.

Comments welcome!

When Law is Code

I have a new Jotwell review of Sarah Lawsky’s Coding the Code: Catala and Computationally Accessible Tax Law. It is nominally a review of this recent (outstanding) article, but I used the occasion to go back through her recent body of work and introduce it to a wider audience who may not be aware of the remarkable nature of her project. Here are some excerpts:

Sarah B. Lawsky’s Coding the Code: Catala and Computationally Accessible Tax Law offers an exceptionally thoughtful perspective on the automation of legal rules. It provides not just a nuanced analysis of the consequences of translating legal doctrines into computer programs (something many other scholars have done), but also a tutorial in how to do so effectively, with fidelity to the internal structure of law and humility about what computers do and don’t do well. …

Coding the Code, like the rest of Lawsky’s work, stands out in two ways. First, she is actively making it happen, using her insights as a legal scholar and logician to push forward the state of the art. Her Lawsky Practice Problems site–a hand-coded open source app that can generate as many tax exercises as students have the patience to work through–is a pedagogical gem, because it matches the computer science under the hood to the structure of the legal problem. (Her Teaching Algorithms and Algorithms for Teaching documents the app and why it works the way it does.)

Second, Lawsky’s claims about the broader consequences of formal approaches are grounded in a nuanced understanding of what these formal approaches do well and what they do not. Sometimes formalization leads to insight; her recent Reasoning with Formalized Statutes shows how coding up a statute section can reveal unexpected edge cases and drafting mistakes. At other times, formalization is hiding in plain sight. As she observes in 2020’s Form as Formalization, the IRS already walks taxpayers through tax algorithms; its forms provide step-by-step instruction for making tax computations. In every case, Lawsky links carefully links her systemic claims to specific doctrinal examples. She shows not that computational law will change everything, but rather that it is already changing some things, in ways large and small.

The Files are in the Computer

I have a new draft essay, The Files are in the Computer: On Copyright, Memorization, and Generative AI. It is a joint work with my regular co-author A. Feder Cooper, who just completed his Ph.D. in Computer Science at Cornell. We presented an earlier version of the paper at the online AI Disrupting Law Symposium symposium hosted by the Chicago-Kent Law Review in April, and the final version will come out in the CKLR. Here is the abstract:

The New York Times’s copyright lawsuit against OpenAI and Microsoft alleges that OpenAI’s GPT models have “memorized” Times articles. Other lawsuits make similar claims. But parties, courts, and scholars disagree on what memorization is, whether it is taking place, and what its copyright implications are. Unfortunately, these debates are clouded by deep ambiguities over the nature of “memorization,” leading participants to talk past one another.

In this Essay, we attempt to bring clarity to the conversation over memorization and its relationship to copyright law. Memorization is a highly active area of research in machine learning, and we draw on that literature to pro- vide a firm technical foundation for legal discussions. The core of the Essay is a precise definition of memorization for a legal audience. We say that a model has “memorized” a piece of training data when (1) it is possible to reconstruct from the model (2) a near-exact copy of (3) a substantial portion of (4) that specific piece of training data. We distinguish memorization from “extraction” (in which a user intentionally causes a model to generate a near-exact copy), from “regurgitation” (in which a model generates a near-exact copy, regardless of the user’s intentions), and from “reconstruction” (in which the near-exact copy can be obtained from the model by any means, not necessarily the ordinary generation process).

Several important consequences follow from these definitions. First, not all learning is memorization: much of what generative-AI models do involves generalizing from large amounts of training data, not just memorizing individual pieces of it. Second, memorization occurs when a model is trained; it is not something that happens when a model generates a regurgitated output. Regurgitation is a symptom of memorization in the model, not its cause. Third, when a model has memorized training data, the model is a “copy” of that training data in the sense used by copyright law. Fourth, a model is not like a VCR or other general-purpose copying technology; it is better at generating some types of outputs (possibly including regurgitated ones) than others. Fifth, memorization is not just a phenomenon that is caused by “adversarial” users bent on extraction; it is a capability that is latent in the model itself. Sixth, the amount of training data that a model memorizes is a consequence of choices made in the training process; different decisions about what data to train on and how to train on it can affect what the model memorizes. Seventh, system design choices also matter at generation time. Whether or not a model that has memorized training data actually regurgitates that data depends on the design of the overall system: developers can use other guardrails to prevent extraction and regurgitation. In a very real sense, memorized training data is in the model–to quote Zoolander, the files are in the computer.

Postmodern Community Standards

This is a Jotwell-style review of Kendra Albert, Imagine a Community: Obscenity’s History and Moderating Speech Online_, 25 Yale Journal of Law and Technology Special Issue 59 (2023). I’m a Jotwell reviewer, but I am conflicted out of writing about Albert’s essay there because I co-authored a short piece with them last year. Nonetheless, I enjoyed Imagine a Community so much that I decided to write a review anyway, and post it here.

One of the great non-barking dogs in Internet law is obscenity. The first truly major case in the field was an obscenity case. 1997’s Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844 (1997), held that the harmful-to-minors provisions of the federal Communications Decency Act were unconstitutional because they prevented adults from receiving non-obscene speech online. Several additional Supreme Court cases followed over the next few years, as well as numerous lower-court cases, mostly rejecting various attempts to redraft definitions and prohibitions in a way that would survive constitutional scrutiny.

But then … silence. From roughly the mid-2000s on, very few obscenity cases have generated new law. As a casebook editor, I even started deleting material – this never happens – simply because there was nothing new to teach. This absence was a nagging question in the back of my mind. But now, thanks to Kendra Albert’s Imagine a Community, I have the answer, perfectly obvious now that they have laid it out so clearly. The courts did not give up on obscenity, but they gave up on obscenity law.

Imagine a Community is a cogent exploration of the strange career of community standards in obscenity law. Albert shows that the although the “contemporary community standards” test was invented to provide doctrinal clarity, it has instead been used for doctrinal evasion and obfuscation. Half history and half analysis, their essay is an outstanding example of a recent wave of cogent scholarship on sex, law, and the Internet, from scholars like Albert themself, Andrew Gilden, I. India Thusi, and others.

The historical story proceeds as a five-act tragedy, in which the Supreme Court is brought low by its hubris. In the first act, until the middle of the twentieth century, obscenity law varied widely from state to state and case to case. Then, in the second act, the Warren Court constitutionalized the law of obscenity, holding that whether a work is protected by the First Amendment depends on whether it “appeals to prurient interest” as measured by “contemporary community standards.” Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476, 489 (1957).

This test created two interrelated problems for the Supreme Court. First, it was profoundly ambiguous. Were community standards geographical or temporal, local or national? And second, it required the courts to decide a never-ending stream of obscenity cases. It proved immensely difficult to articulate how works did – or did not – comport with community standards, leading to embarrassments of reasoned explication like Potter Stewart’s “I know it when I see it” in Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 197 (1964).

The Supreme Court was increasingly uncomfortable with these cases, but it was also unwilling to deconstitutionalize obscenity or to abandon the community-standards test. Instead, in Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973), it threw up its hands and turned community standards into a factual question for the jury. As Albert explains, “The local community standard won because it was not possible to imagine what a national standard would be.”

The historian S.F.C. Milsom blamed “the miserable history of crime in England” on the “blankness of the general verdict” (Historical Foundations of the Common Law pp. 403, 413). There could be no substantive legal development unless judges engaged with the facts of individual cases, but the jury in effect hid all of the relevant facts behind a simple “guilty” or “not guilty.”

Albert shows that something similar happened in obscenity law’s third act. The jury’s verdict established that the defendant’s material did or did not appeal to the prurient interest according to contemporary standards. But it did so without ever saying out loud what those standards were. There were still obscenity prosecutions, and there were still obscenity convictions, but in a crucial sense there was much less obscenity law.

In the fourth act, the Internet unsettled a key assumption underpinning the theory that obscenity was a question of local community standards: that every communication had a unique location. The Internet created new kinds of online communities, but it also dissolved the informational boundaries of physical ones. Is a website published everywhere, and thus subject to every township, village, and borough’s standards? Or was a national rule now required? In the 2000s, courts wrestled inconclusively with the question of “Who gets to decide what is too risqué for the Internet?”

And then, Albert demonstrates, in the tragedy’s fifth and deeply ironic act, prosecutors gave up the fight. They have largely avoided bringing adult Internet obscenity cases, focusing instead on child sexual abuse material cases and on cases involving “local businesses where the question of what the appropriate community was much less fraught.” The community-standards timbers have rotted, but no one has paid it much attention because they are not bearing any weight.

This history is a springboard for two perceptive closing sections. First, Albert shows that the community-standards-based obscenity test is extremely hard to justify on its own terms, when measured against contemporary First Amendment standards. It has endured not because it is correct but because it is useful. “The ‘community’ allows courts to avoid the reality that obscenity is a First Amendment doctrine designed to do exactly what justices have decried in other contexts – have the state decide ‘good speech’ from ‘bad speech’ based on preference for certain speakers and messages.” Once you see the point put this way, it is obvious – and it is also obvious that this is the only way this story could have ever ended.

Second – and this is the part that makes this essay truly next-level – Albert describes the tragedy’s farcical coda. The void created by this judicial retreat has been filled by private actors. Social-media platforms, payment providers, and other online intermediaries have developed content-moderation rules on sexually explicit material. These rules sometimes mirror the vestigial conceptual architecture of obscenity law, but often they are simply made up. Doctrine abhors a vacuum:

Pornography producers and porn platforms received lists of allowed and disallowed words and content – from “twink” to “golden showers,” to how many fingers a performer might use in a penetration scene. Rules against bodily fluids other than semen, even the appearance of intoxication, or certain kinds of suggestions of non-consent (such as hypnosis) are common.

One irony of this shift from public to private is that it has done what the courts have been unwilling to: create a genuinely national (sometimes even international) set of rules. Another is that these new “community standards” – a term used by social-media platforms apparently without irony – are applied without any real sensitivity to the actual standards of actual community members. They are simply the diktats of powerful platforms.

Perhaps none of this will matter. Albert suggests that the Supreme Court should perhaps “reconsider[] whether obscenity should be outside the reach of the First Amendment altogether.” Maybe it will, and maybe the legal system will catch up to the Avenue Q slogan: “The Internet is for porn.”

But there is another and darker possibility. The law of public sexuality in the United States has taken a turn over the last few years. Conservative legislators and prosecutors have claimed with a straight face that drag shows, queer romances, and trans bodies are inherently obscene. A new wave of age-verification laws sharply restrict what children are allowed to read on the Internet, and force adults to undergo new levels of surveillance when they go online. It is unsettlingly possible that the Supreme Court may be about to speedrun its obscenity jurisprudence, only backwards and in heels.

But sufficient unto the day is the evil thereof. For now, Imagine a Community is a model for what a law-review essay should be: concise, elegant, and illuminating.

How Licenses Learn

I have posted a new draft essay, How Licenses Learn. It is a joint work with Madiha Zahrah Choksi, a Ph.D. student in Information Science at Cornell Tech, and the paper itself is an extended and enriched version of her seminar paper from my Law of Software course from last spring. We presented it at the Data in Business and Society symposium at Lewis and Clark Law School in September, and the essay is forthcoming in the Lewis and Clark Law Review later this year.

Here is the abstract:

Open-source licenses are infrastructure that collaborative communities inhabit. These licenses don’t just define the legal terms under which members (and outsiders) can use and build on the contributions of others. They also reflect a community’s consensus on the reciprocal obligations that define it as a community. A license is a statement of values, in legally executable form, adapted for daily use. As such, a license must be designed, much as the software and hardware that open-source developers create. Sometimes an existing license is fit to purpose and can be adopted without extensive discussion. However, often the technical and social needs of a community do not precisely map onto existing licenses, or the community itself is divided about the norms a license should enforce. In these cases of breakdown, the community itself must debate and design its license, using the same social processes it uses to debate and design the other infrastructure it relies on, and the final goods it creates.

In this Article, we analyze four case studies of controversy over license design in open-source software and hardware ecosystems. We draw on Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn, a study of how physical buildings change over time as they are adapted and repurposed to deal with new circumstances by successive generations of users. Similarly, we describe how open-source licenses are adapted and repurposed by different communities confronting challenges. Debates over license drafting and interpretation are a key mechanism of achieving the necessary consensus for successful collaboration. The resulting licenses are the visible traces of the constant political work that sustains open-source collaboration. Successful licenses, like successful buildings, require ongoing maintenance, and the record of license changes over the years is a history of the communities that have inhabited them.

The paper has been a great pleasure to work on for many reasons. First and foremost is the joy of collaborative work. Madiha has done extensive research on how open-source communities handle both cooperation and conflict, and the stories in How Licenses Learn are just a small fraction of the ones she has studied. Like the communities she studies, Madiha engages with legal issues from the perspective of a well-informed non-lawyer, which helps a lot in understanding what is really going on in arguments over licensing.

Second, this paper was a chance for me to revisit some of the ideas in architectural theory that I have been chewing on since I wrote Regulation by Software in law school nearly 20 years ago. Larry Lessig famously connected software to architecture, and we found the metaphor illuminating in thinking about the ``architecture’’ of software licensing. As always, I hope you enjoy reading this as much as I—as we—enjoyed writing it.

Scholars' Amicus Brief in the NetChoice Cases

Yesterday, along with twenty colleagues — in particular Gautam Hans, who served as counsel of record — I filed an amicus brief in the Supreme Court’s cases on Florida and Texas’s anti-content-moderation social-media laws, Moody v. NetChoice and NetChoice v. Paxton. The cases involve First Amendment challenges to laws that would prohibit platforms from wide swaths of content moderation. Florida’s prohibits removing or downranking any content posted by journalistic enterprises or by or about candidates for public office; Texas’s prohibits any viewpoint-based moderation of any content at all.

Our brief argues that these laws are unconstitutional restrictions on the rights of social-media users to find and receive the speech that they want to listen to. By prohibiting most content moderation, they force platforms to show users floods of content those users find repugnant, or are simply not interested in. This, we claim, is a form of compelled listening in violation of the First Amendment.

Here is the summary of our argument:

This case raises complex questions about social-media platforms’ First Amendment rights. But Florida Senate Bill 7072 (SB 7072) and Texas House Bill 20 (HB 20) also severely restrict platform users’ First Amendment rights to select the speech they listen to. Any question here is straightforward: such intrusions on listeners’ rights are flagrantly unconstitutional.

SB 7072 and HB 20 are the most radical experiments in compelled listening in United States history. These laws would force millions of Internet users to read billions of posts they have no interest in or affirmatively wish to avoid. This is compulsory, indiscriminate listening on a mass scale, and it is flagrantly unconstitutional.

Users rely on platforms’ content moderation to cope with the overwhelming volume of speech on the Internet. When platforms prevent unwanted posts from showing up in users’ feeds, they are not engaged in censorship. Quite the contrary. They are protecting users from a neverending torrent of harassment, spam, fraud, pornography, and other abuse — as well as material that is perfectly innocuous but simply not of interest to particular users. Indeed, if platforms did not engage in these forms of moderation against unwanted speech, the Internet would be completely unusable, because users would be unable to locate and listen to the speech they do want to receive.

Although these laws purport to impose neutrality among speakers, their true effect is to systematically favor speakers over listeners. SB 7072 and HB 20 pre- vent platforms from routing speech to users who want it and away from users who do not. They convert speakers’ undisputed First Amendment right to speak without government interference into something much stronger and far more dangerous: an absolute right for speakers to have their speech successfully thrust upon users, despite those users’ best efforts to avoid it.

In the entire history of the First Amendment, listeners have always had the freedom to seek out the speech of their choice. The content-moderation restrictions of SB 7072 and HB 20 take away that freedom. On that basis alone, they can and should be held unconstitutional.

This brief brings together nearly two decades of my thinking about Internet platforms, and while I’m sorry that it has been necessary to get involved in this litigation, I’m heartened at the breadth and depth of scholars who have joined together to make sure that users are heard. On a day when it felt like everyone was criticizing universities over their positions on free speech, it was good to be able to use my position at a university to take a public stand on behalf of free speech against one of its biggest threats: censorious state governments.

Talkin' `Bout AI Generation

I have a new draft paper with Katherine Lee and A. Feder Cooper on copyright and generative AI: Talkin’ ‘Bout AI Generation: Copyright and the Generative AI Supply Chain. The essay maps out the different legal issues that bear on whether datasets, models, services, and generations infringe on the copyrights in training data. (Spoiler alert: there are a lot of issues.) Here is the abstract:

This essay is an attempt to work systematically through the copyright infringement analysis of the generative AI supply chain. Our goal is not to provide a definitive answer as to whether and when training or using a generative AI is infringing conduct. Rather, we aim to map the surprisingly large number of live copyright issues that generative AI raises, and to identify the key decision points at which the analysis forks in interesting ways.

I know that I say that every paper was especially fun to work on. This one too. Katherine and Cooper are computer scientists who work on machine learning, I am the law-talking guy, and every single paragraph in the paper reflects something that one or more of us learned while writing it.

Content Moderation on End-to-End Encrypted Systems

I have a new draft article with Charles Duan, Content Moderation on End-to-End Encrypted Systems. A group of us received an NSF grant to study techniques for preventing abuse in encrypted messaging systems without compromising their privacy guarantees. Charles and I have been looking how these techniques interact with communications privacy laws, which were written decades ago, long before some of the cryptographic tools had been invented.

This paper has been a lot of fun to work on. Charles and I are birds of a feather; we enjoy spending time at the intersection of law and computer science. Although the details of the analysis are highly technical (in both legal and technological senses), working through them led us to some interesting observations about end-to-end encryption and the structure of the federal communications privacy laws.

Here is the abstract:

End-to-end encrypted online platforms are increasingly common in the digital ecosystem, found both in dedicated apps like Signal and widely adopted platforms like Android Messages. Though such encryption protects privacy and advances human rights, the law enforcement community and others have raised criticisms that end-to-end encryption shields bad behavior, preventing the platforms or government authorities from intercepting and responding to criminal activity, child exploitation, malware scams, and disinformation campaigns. At a time when major Internet platforms are under scrutiny for content moderation practices, the question of whether end-to-end encryption interferes with effective content moderation is of serious concern.

Computer science researchers have responded to this challenge with a suite of technologies that enable content moderation on end-to-end encrypted platforms. Are these new technologies legal? This Article analyzes these new technologies in light of several major federal communication privacy regimes: the Wiretap Act, the Stored Communications Act, and the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act.

While generally we find that these content moderation technologies would pass muster under these statutes, the answers are not as clear-cut as one might hope. The advanced cryptographic techniques that these new content moderation strategies employ raise multiple unsettled questions of law under the communication privacy regimes considered. This legal uncertainty arises not because of the ambiguous ethical nature of the technologies themselves, but because the decades-old statutes failed to accommodate, or indeed contemplate, the innovations in cryptography that enable content moderation to coexist with encryption. To the extent that platforms are limited in their ability to moderate end-to-end encrypted content, then, those limits may arise not from the technology but from the law.

Comments welcome!

An Economic Model of Intermediary Liability

I have posted a draft of a new article, An Economic Model of Intermediary Liability. It’s a collaboration with Pengfei Zhang, who I met when he was a graduate student in economics at Cornell, and is now a professor at UT Dallas. He was studying the economics of content takedowns, and participated in my content-moderation reading group. We fell to talking about how to model different intermediary liability regimes, and after a lot of whiteboard diagrams, this paper was the result. I presented it at the Berkeley Center for Law & Technology Digital Services Act Symposium, and the final version will be published in the Berkeley Technology Law Journal later this year.

I’m excited about this work for two reasons. First, I think we have developed a model that hits the sweet spot between elegance and expressiveness. It has only a small number of moving parts, but the model demonstrates off all of the standard tropes of the debates around intermediary liability: collateral censorship, the moderator’s dilemma, the tradeoffs between over- and under-moderation, and more. It can describe a wide range of liability regimes, and should be a useful foundation for future economic analysis of online liability rules. Second, there are really pretty pictures. Our diagrams make these effects visually apparent; I hope they will be useful in building intuition and in thinking about the design of effective regulatory regimes.

Here is the abstract:

Scholars have debated the costs and benefits of Internet intermediary liability for decades. Many of their arguments rest on informal economic arguments about the effects of different liability rules. Some scholars argue that broad immunity is necessary to prevent overmoderation; others argue that liability is necessary to prevent undermoderation. These are economic questions, but they rarely receive economic answers.

In this paper, we seek to illuminate these debates by giving a formal economic model of intermediary liability. The key features of our model are externalities, imperfect information, and investigation costs. A platform hosts user-submitted content, but it does not know which of that content is harmful to society and which is beneficial. Instead, the platform observes only the probability that each item is harmful. Based on that knowledge, it can choose to take the content down, leave the content up, or incur a cost to determine with certainty whether it is harmful. The platform’s choice reflects the tradeoffs inherent in content moderation: between false positives and false negatives, and between scalable but more error-prone processes and more intensive but costly human review.

We analyze various plausible legal regimes, including strict liability, negligence, blanket immunity, conditional immunity, liability on notice, subsidies, and must carry, and we use the results of this analysis to describe current and proposed laws in the United States and European Union.

We will have an opportunity to make revisions, so comments are eagerly welcomed!

Programming Property Law

One of the things that sent me to law school was finding a used copy of Jesse Dukeminier and James Krier’s casebook Property in a Seattle bookstore. It convinced me – at the time a professional programmer – that the actual, doctrinal study of law might be intellectually rewarding. (I wonder how my life might have turned out if I had picked up a less entertaining casebook.)

Although everything it was interesting, one section in particular stood out. Like every Property book, Dukeminier and Krier’s book devoted several central chapters to the intricate set of rules that govern how ownership of real estate can be divided up among different owners across time. If the owner of a parcel of land executes a deed transferring it “to Alice for life, and then to Bob and his heirs,” then Alice will have the right to enter on the land, live on it, grow crops, and so on for as long as she lives. At her death, automatically and without any need of action on anyone’s part, Alice’s rights will terminate and Bob will be entitled to enter on the land, live on it, grow crops, and so on. As Dukeminer and Krier patiently explain, Alice is said to have an interest called a “life estate” and Bob a “remainder.” There are more of these rules – many, many more of them – and they can be remarkably complicated, to the point that law students sometimes buy study aids to help them specifically with this part of the Property course.

There is something else striking about this system of “estates in land and future interests.” Other parts of the Property course are like most of law school; they involve the analogical process identifying factual similarities and differences between one case and another. But the doctrines of future interests are different. At least in the form that law students learn them, they are about the mechanical application of precise, interlocking rules. Other students find it notoriously frustrating. As a computer scientist, I found it fascinating. I loved all of law school, but I loved this part more than anything else. It was familiar.

The stylized language of conveyances like “to Alice for life, and then to Bob and his heirs” is a special kind of legal language – it is a programming language. The phrase “for life” is a keyword; the phrase “to Alice for life” is an expression. Each of them has a precise meaning. We can combine these expressions in specific, well-defined ways to build up larger expressions like “to Alice for life, then to Bob for life, then to Carol for life.” Centuries of judicial standardization have honed the rules of the system of future of estates; decades of legal education has given those rules clear and simple form.

In 2016, after I came to Cornell, I talked through some of these ideas with a creative and thoughtful computer-science graduate student, Shrutarshi Basu (currently faculty at Middlebury). If future interests were a programming language, we realized, we could define that language, such that “programs” like O conveys to Alice for life, then to Bob and his heirs. Alice dies. would have a well-defined meaning – in this case Bob owns a fee simple. We brought on board Basu’s advisor Nate Foster, who worked with us to nail down the formal semantics of this new programming language. Three more of Nate’s students – Anshuman Mohan, Shan Parikh, and Ryan Richardson – joined to help with programming the implementation.

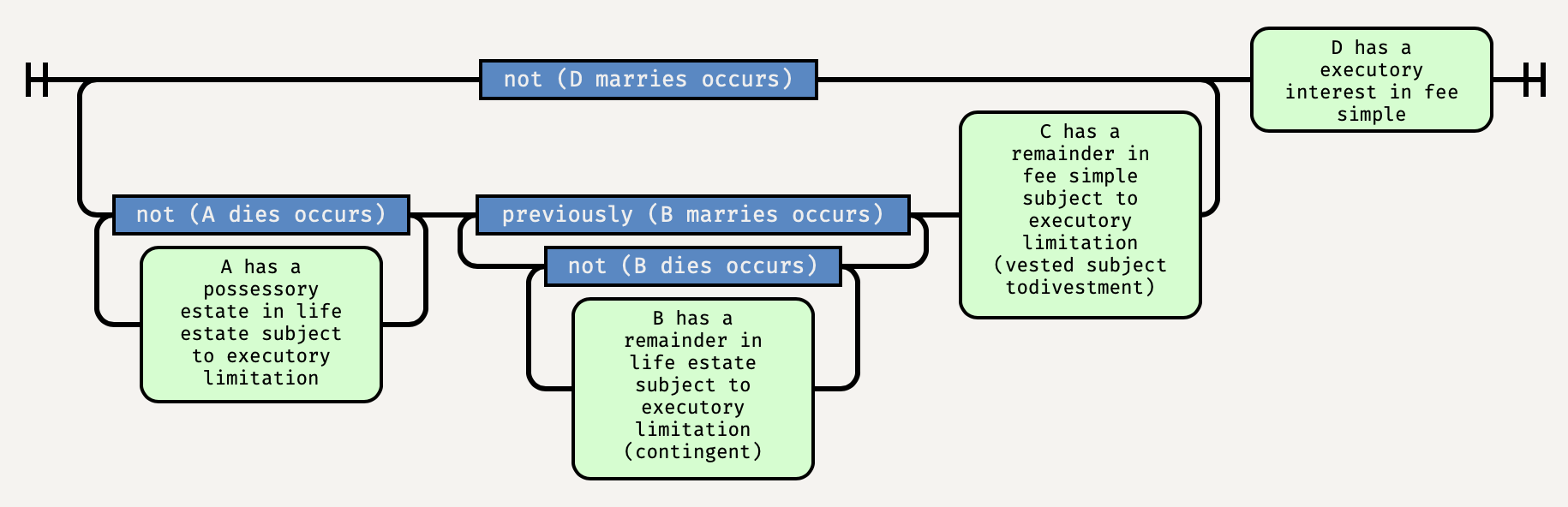

I am happy to announce, that following six years of work, we have developed a new way of understanding future interests. We have defined a new programming language, which we call Orlando (for Orlando Bridgeman), that expresses the formalized language of Anglo-American real-property conveyances. And we have implemented that language in a system we call Littleton (for Thomas de Littleton of the Treatise on Tenures), a program that parses and analyzes property conveyances, translating them from stylized legal text like

O conveys Blackacre to A for life, then to B for life if B is married, then to C, but if D marries to D.

into simple graphs like

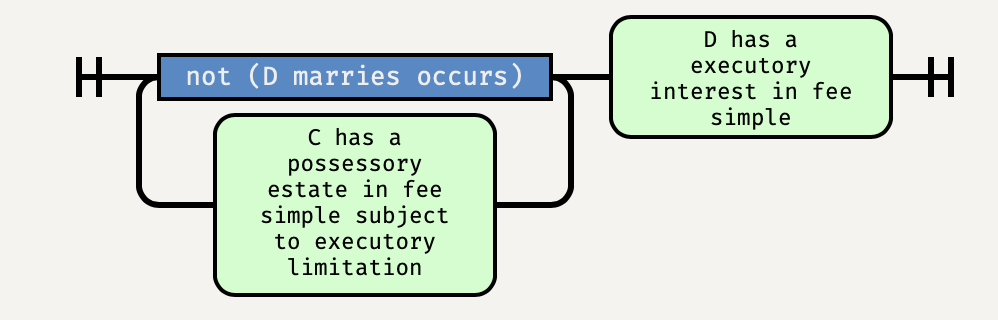

Then, if something else happens, such as

A dies.

Littleton updates the state of title, in this case to:

Littleton and Orlando model almost everything in the estates-in-land-and-future-interests portion of the first-year Property curriculum, including life estates, fees tail, terms of years, remainders and reversions, conditions subsequent and precedent, executory limitations and interests, class gifts, the Doctrine of Worthier Title and the Rule in Shelley’s case, merger, basic Rule Against Perpetuities problems, joint tenancies and tenancies in common, and the basics of wills and intestacy. They are no substitute for a trained and experienced lawyer, but they can do most of what we we expect law students to learn in their first course in the subject.

We have put a version of Littleton online, where anyone can use it. The Littleton interpreter includes a rich set of examples that anyone can modify and experiment with. It comes with includes a online textbook, Interactive Future Interests, that covers the standard elements of a Property curriculum. Property teachers and students can use it to explain, visualize, and explore the different kinds of conveyances and interests that first-year Property students learn. We hope that these tools will be useful for teaching and learning the rules that generations of law students have struggled with.

To enable others to build on our work and implement their own property-law tools, we have put online the Littleton source code and released it under an open-source license. Anyone can install it on their own computer or create their own online resources. And anyone can modify it to develop their own computerized interpretation of property law.

To share the lessons we have learned from developing Orlando and Littleton, we have published two articles describing them in detail. The first, Property Conveyances as a Programming Language, published in the conference proceedings of the Onward! programming-language symposium, is directed at computer scientists. It gives formal, mathematical semantics for the core of Orlando, and shows that it captures essential features of property law, such as nemo dat quot non habet. The second, A Programming Language for Future Interests, published in the Yale Journal of Law and Technology, is directed at legal scholars. It explains how Orlando and Littleton work, and describes the advantages of formalizing property law as a programming language. As we say in the conclusion:

To quote the computer scientist Donald Knuth, “Science is what we understand well enough to explain to a computer. Art is everything else we do.” For centuries, future interests have been an arcane art. Now they are a science.

Data Property

Christina Mulligan and I have a new paper, Data Property. Here’s the abstract:

In this, the Information Age, people and businesses depend on data. From your family photos to Google’s search index, data has become one of society’s most important resources. But there is a gaping hole in the law’s treatment of data. If someone destroys your car, that is the tort of conversion and the law gives a remedy. But if someone deletes your data, it is far from clear that they have done you a legally actionable wrong. If you are lucky, and the data was stored on your own computer, you may be able to sue them for trespass to a tangible chattel. But property law does not recognize the intangible data itself as a thing that can be impaired or converted, even though it is the data that you care about, and not the medium on which it is stored. It’s time to fix that.

This Article proposes, explains, and defends a system of property rights in data. On our theory, a person has possession of data when they control at least one copy of the data. A person who interferes with that possession can be liable, just as they can be liable for interference with possession of real property and tangible personal property. This treatment of data as an intangible thing that is instantiated in tangible copies coheres with the law’s treatment of information protected by intellectual property law. But importantly, it does not constitute an expansive new intellectual property right of the sort that scholars have warned against. Instead, a regime of data property fits comfortably into existing personal-property law, restoring a balanced and even treatment of the different kinds of things that matter for people’s lives and livelihoods.

The article is forthcoming in early 2023 in the American University Law Review. Comments welcome!

There's No Justice Like Angry Mob Justice

This post was originally written as a review for The Journal of Things We Like Lots, but was not published there because reasons. I am posting it here to help an excellent work of scholarship receive the recognition and readership it deserves.

The Internet is using you. Every time you post and comment, every time you like and subscribe, yes you are using the Internet to express a bit of yourself, but it is also extracting that bit of you, and melting it down into something strange and new. That story you forwarded was misinformation, that video you loved was a publicity stunt, that quiz trained an AI model, and that tweet you just dunked on was from someone who’s going to have to delete their account to deal with the waves of hate.

Alice Marwick’s Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement, Social Media + Society, Apr.-June 2021, at 1, is an illuminating analysis of how online mobs come together to attack a target. Building on interviews with harassment victims and trust-and-safety professionals, she describes the social dynamics of the outrage cycle with empathy and precision. The “networked” part of her framing, in particular, has important implications for content moderation and social-media regulation.

Marwick’s model of morally motivated networked harassment (or “MMNH”) is simple and powerful:

[A] member of a social network or online community accuses an individual (less commonly a brand or organization) of violating the network’s moral norms. Frequently, the accusation is amplified by a highly followed network node, triggering moral outrage throughout the networked audience. Members of the network send harassing messages to the individual, reinforcing their own adherence to the norm and signaling network membership, thus re-inscribing the norm and reinforcing the network’s values.

Three features of the MMNH model are particularly helpful in understanding patterns of online harassment: the users’ moral motivations, the catalyzing role of the amplifying node, and the networked nature of the harassment.

First, the moral motivations are central to the toxicity of online harassment. Debates about the blue-or-white dress went viral, but because color perception usually has no particular moral significance, the arguments were mostly civil. Similarly, the moral framing explains why particular incidents blow up in the first place, and the nature of the rhetoric used when they do. People get angry at what they perceive as violations of shared moral norms, and they feel justified in publicly expressing that anger. Indeed, because morality involves the interests and values of groups larger than the individual, participants can feel that getting righteously mad is an act of selfless solidarity; it affirms their membership in something larger than themselves.

Second, Marwick identifies the catalytic role played by “highly followed network node[s].” Whether they are right-wing YouTubers accusing liberals of racism or makeup influencers accusing each other of gaslighting, they help to focus a community’s diffuse attention on a specific target and to crystalize its condemnation around specific perceived moral violations. These nodes might be already-influential users, like a “big name fan” within a fan community. In other cases, they serve as focal points for collective identity formation through MMNH itself: they are famous and followed in part because they direct their followers to a steady stream of harassment targets.

Third and most significantly, the MMNH model highlights the genuinely networked character of this harassment. It is not just that it takes place on a much greater scale than an individual stalker can inflict. Instead, participants see themselves as part of a collective and act accordingly; each individual act of aggression helps to reinforce the shared norm that something has happened here that is worthy of aggression. Online mobs offer psychological and social benefits to their members, and Marwick’s theory helps make sense of this particular mob mentality.

The MMNH model has important implications for content moderation and platform regulation. One point is that the perception of being part of a community with shared values under urgent threat matters greatly. Even when platforms are unwilling to remove individual posts that do not cross the line into actionable harassment, they should pay attention to how their recommendation and sharing mechanisms facilitate the formation of morally motivated networks. Of course, morally motivating messages are often the ones that drive engagement – but this is just another reminder that engagement is the golden calf at which platforms worship.

Similarly, the outsize role that influencers, trolls, and other highly followed network nodes play in driving networked harassment is an uncomfortable fact for legal efforts to mitigate its harms. As Marwick and others have documented, it is often enough for these leaders to describe a target’s behavior as a moral transgression, leaving the rest unsaid. Their followers and their networks take the next step of carrying out the harassment. One possibility is that MMNH is such a consistent pattern that certain kinds of morally freighted callouts should be recognized as directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action, even when they say nothing explicit about defamation, doxxing, and death threats. “[I]n the surrounding circumstances the likelihood was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it,” we might say.

Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement is a depressing read. Marwick describes people at their worst. The irony is that harassers’ spittle-flecked outrage arises because of their attempts to be moral people online, not in spite of it. We scare because we care.

CPU, Esq.

I am writing a book. It is the book I have been working towards, not always consciously, for a decade. It is the book I was born to write.

The tentative title is CPU, Esq.: How Lawyers and Coders Do Things with Words. It tackles a very familiar question in technology law: what is the relationship between law and software?. But it comes at the problem from what I think is a new and promising direction: the philosophy of language. As I put it in the abstract:

Should law be more like software? Some scholars say yes, others say no. But what if the two are more alike than we realize?

Lawyers write statutes and contracts. Programmers write software. Both of them use words to do things in the world. The difference is that lawyers use natural language with all its nuances and ambiguities, while programmers use programming languages, which promise the rigor of mathematics. Could legal interpretation be more objective and precise if it were more like software interpretation, or would it give up something essential in the attempt?

CPU, Esq. explodes the idea that law can escape its problems by turning into software. It uses ideas from the philosophy of language to show that software and law are already more alike than they seem, because software also rests on social foundations. Behind the apparent exactitude of 1s and 0s, programmers and users are constantly renegotiating the meanings of programs, just as lawyers and judges are constantly renegotiating the meanings of legal texts. Law can learn from software, and software can learn from law. But law cannot become what it thinks software is – because not even software actually works that way.

The book stands on three legs: law, software, and philosophy. Each pair of this triad has been explored: the philosophy of law, the law of software, and the philosophy of software. But never, to my knowledge, have they been considered all at once. More specifically, I plan to:

- Use concepts from the philosophy of law – particularly the theory of speech acts and legal interpretation – to give a rigorous account of how software works

- Use that account to illuminate questions in legal doctrine: e.g., how should judges interpret smart contracts?

- Use that account to illuminate questions in legal theory: e.g., is the ideal judge a computer?

CPU, Esq. is under contract with Oxford University Press, and I will be on sabbatical in 2020-21 writing it. If you are interested, the book has its own site and I also have a mailing list where I will post updates, research queries, and requests for feedback. If this sounds interesting to you, please sign up!

Spyware vs. Spyware

I’m happy to announce a little non-coronavirus news. I gave a lecture at Ohio State in the fall for the 15th anniversary of their newly renamed Ohio State Technology Law Journal. It was a great program: Mary Anne Franks gave the other lecture and there were some unexpected but fascinating connections between our talks. My remarks have been going through the editorial pipeline, and just today the student editors emailed me the final PDF of the essay. And so I give you Spyware vs. Spyware: Software Conflicts and User Autonomy.

By remarkable coincidence, my talk started with … a massive Zoom privacy hole.

This is the story of the time that Apple broke Zoom, and everybody was surprisingly okay with it. The short version is that Zoom provides one of the most widely used video-conferencing systems in the world. One reason for Zoom’s popularity is its ease of use; one reason Zoom was easy to use was that it had a feature that let users join calls with a single click. On macOS, Zoom implemented this feature by running a custom web server on users’ computers; the server would receive Zoom-specific requests and respond by launching Zoom and connecting to the call. Security researchers realized that that web pages could use this feature to join users to Zoom calls without any further confirmation on their part, potentially enabling surveillance through their webcams and microphones. The researchers released a proof-of-concept exploit in the form of a webpage that would immediately connect anyone who visited it to a Zoom video call with random strangers. They also sketched out ways in which the Zoom server on users’ computers could potentially be used to hijack those computers into running arbitrary code.

After the story came to light, Apple’s response was swift and unsparing. It pushed out a software update to macOS to delete the Zoom server and prevent it from being reinstalled. The update was remarkable, and not just because it removed functionality rather than adding it. Typical Apple updates to macOS show a pop-up notification that lets users choose whether and when to install an update. But Apple pushed out this update silently and automatically; users woke up to discover that the update had already been installed—if they discovered it at all. In other words, Apple deliberately broke an application feature on millions of users’ computers without notice or specific consent. And then, six days later, Apple did it again.

There is a lot that could be said about this episode; it illuminates everything from responsible disclosure practices to corporate public relations to secure interface design for omnipresent cameras and microphones. But I want to dwell on just how strange it is that one major technology company (AAPL, market capitalization $1.4 trillion) deliberately broke a feature in another major technology company’s (ZM, market capitalization $24 billion) product for millions of users, and almost no one even blinked. We are living in a William Gibson future of megacorporations waging digital warfare on each other’s software and everyone just accepts that this is how life is now.

Here is the abstract:

In July 2019, Apple silently updated macOS to uninstall a feature in the Zoom webconferencing software from users’ computers. Far from being an abberation, this is an example of a common but under-appreciated pattern. Numerous programs deliberately delete or interfere with each other, raising a bewildering variety of legal issues.

Unfortunately, the most common heuristics for resolving disputes about what software can and cannot do fail badly on software-versus-software conflicts. Bad Software Is Bad, which holds that regulators should distinguish helpful software from harmful software, has a surprisingly hard time telling the difference. So does Software Freedom, which holds that users should have the liberty to run any software they want: it cannot by itself explain what software users actually want. And Click to Agree, which holds that users should be held to the terms of the contracts they accept, falls for deceptive tricks, like the the virus with a EULA. Each of these heuristics contains a core of wisdom, but each is incomplete on its own.

To make sense of software conflicts, we need a theory of user autonomy, one that connects users’ goals to their choices about software. Law should help users delegate important tasks to software. To do so, it must accept the diversity of users’ skills and goals, be realistic about which user actions reflect genuine choices, and pay close attention to the communicative content of software.

Bone Crusher 2.0

Greg Lastowka, who taught law at Rutgers-Camden until his untimely death of cancer in 2015, was a thoughtful scholar of copyright and virtual worlds, a beloved teacher, and a profoundly decent human being. He was generous and welcoming to me as a law student whose interests paralleled his, and then a generous and welcoming colleague. He was always one of my favorite people to see at conferences, and his papers were like the man: intelligent, unpretentious, and empathetic, with a twinkle of poetry.

Greg colleagues at Rutgers-Camden have honored his memory by holding an annual memorial lecture, and I was privileged beyond words to be asked to deliver last fall’s fourth annual lecture. It was a snowy day, and I drove through a blizzard to be there. I felt I owed him nothing less. So did many of his colleagues and family, who turned out for the lecture and reception. It was a sad occasion, but also a happy one, to be able to remember with each other what made Greg so special.

I am very pleased to say that thanks to the efforts of many – our mutual friend Michael Carrier from the Rutgers faculty; Alexis Way, the Camden editor-in-chief of volume 70 of the Rutgers University Law Review; her successor Alaina Billingham from volume 71; and the diligent student editors of the RULR – my lecture in memory of Greg has now been published as Bone Crusher 2.0. (The title refers to one of my favorite examples from all of Greg’s scholarship, a stolen Bone Crusher mace from Ultima Online.) Here is the abstract:

The late and much-missed Greg Lastowka was a treasured colleague. Three themes from his groundbreaking scholarship on virtual worlds have enduring relevance. First, virtual worlds are real places. They may not exist in our physical world, but real people spend real time together in them. Second, communities need laws. People in these spaces do harmful things to each other, and we need some rules of conduct to guide them. Third, those laws cannot be the same as the ones we use for offline conduct. Laws must reflect reality, which in this case means virtual reality. Using these three themes as guideposts, we can draw a line from Greg’s work on virtual items in online games – Bone Crusher 1.0 – to modern controversies over virtual assets on blockchains – Bone Crusher 2.0.

This is not my most ambitious paper. But for obvious reasons, it is one of the most personally meaningful. I hope that it brings some readers fond memories of Greg, and introduces others to the work of this remarkable scholar.

Internet Law: Cases and Problems (9th ed.)

The Ninth Edition of Internet Law: Cases and Problems is now available. It includes a new section on platforms as marketplaces, a half-dozen new cases, and updated notes, questions, and problems throughout. As always, the book can be downloaded directly from Semaphore Press as a pay-what-you-want DRM-free PDF. The suggested price to students remains $30. It’s also available as a print-on-demand paperback (this year’s cover color: purple) for $65.50.

Continuity and Change

I am pleased to say that I have joined the editorial board of the Communications of the ACM, the monthly journal of the world’s leading computer-science professional society, the Association for Computing Machinery. I am responsible for editing a three-times-annual column, “Viewpoints: Law and Technology.” The column was created in its modern form by the estimable Stefan Bechtold, and he has done a great job getting a a group of very smart people to write very smart columns. (The estimable Pamela Samuelson single-handedly writes a regular column for CACM as well.) I have big shoes to fill.

This is personally quite meaningful to me. As regular readers of this blog know, bringing law and computer science closer together is my life’s work. It’s hard to think of a more visible symbol of that intersection than the law-focused column of this venerable computer-science journal. I am humbled to have been asked to do this and I have high ambitions to present cutting-edge issues in law and policy to CACM’s readership in a nuanced but accessible way.

There are some great columns by scholars I deeply respect in the editorial pipeline, but to mark the transition, I thought I would take the pen myself to reflect on where Internet law stands today. My inaugural column is titled Continuity and Change in Internet Law, and here is an excerpt:

Everything old is also new again with cryptocurrencies. People have hoped or feared for years that strong cryptography and a global network would make it impossible for governments to control the flow of money. There is a direct line from 1990s-era cypherpunk crypto-anarchism and experiments with digital cash to Bitcoin and blockchains. The regulatory disputes are almost exactly the ones that technologists and lawyers anticipated two decades ago. They just took a little longer to arrive than expected.

In other ways, things look very different today. One dominant idea of the early days of Internet law was that the Internet was a genuinely new place free from government power. As John Perry Barlow wrote in his famous 1996 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace”: “Governments of the Industrial World, you weary giants of flesh and steel, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of Mind. … You have no sovereignty where we gather. … Cyberspace does not lie within your borders.”

If there was a moment that this Matrix-esque vision was definitively unplugged, it was probably the 2003 decision in Intel v. Hamidi. Intel tried to argue that its email servers were a virtual, inviolate space—so that a disgruntled ex-employee who sent email messages to current employees was engaged in the equivalent of breaking into Intel buildings and hijacking its mail carts. The court had no interest in the cyber-spatial metaphor. Instead, it focused on more down-to-earth matters: Intel’s servers were not damaged or knocked offline.

“Cyberspace” turned out not to be a good description of how people use the Internet or what they want from it. Most Internet lawsuits involve familiar real-world problems—ugly divorces, workplace harassment, frauds and scams, and an endless parade of drug deals—that have spilled over onto cellphones, Facebook pages, and other digital platforms.

Whatever developments the years ahead may bring for law and computer science, I look forward to helping the legal and technical communities to understand them by helping CACM carry on its editorial tradition of excellence.

Renvoi and the Barber

I have a new essay, Renvoi and the Barber, in The Green Bag 2d,1. Here is the abstract:

The renvoi paradox in choice of law arises when two states’ laws each purport to select the other’s law. The barber paradox in the foundations of mathematics arises when a set is defined to contain all sets that do not contain themselves, or, more famously, when a barber shaves all men who do not shave themselves. Which state’s law applies? Does the set contain itself? Does the barber shave himself? Each answer implies its opposite.

Conflict of laws is not mathematics, but it could learn from how mathematicians escape the barber paradox: by modifying their theories to to exclude the kind of self-reference that can go so badly wrong. Renvoi too is a paradox of self-reference. Ordinary choice of law blows up into paradox not when one state’s laws refer to another’s, but when a single state’s laws refer back to themselves. The purpose of renvoi rules is to prevent this paradoxical self-reference from occurring; they work by ignoring some aspect of a state’s laws. When a choice-of-law rule selects a state’s law, it always necessarily selects something less than whole law.

The essay also features a dozen diagrams, extensive Sweeney Todd references, some subtle shade on your favorite choice-of-law methodology, and discussion of restricted and unrestricted versions of the Axiom of Comprehension.2 It may be the nerdiest thing I have ever written, and I do not say that lightly.

The Green Bag, like this blog, is in its second series. ↩︎

Which explains some of my previous reading. ↩︎

Internet Law: Cases and Problems (8th ed.)

I have released a new edition of my Internet law casebook. While I revise and update the book every summer, this is an unusually big revision. I had had the feeling that the subject was slipping through my fingers and maybe no longer made sense, so I did a lot of soul-searching in thinking about what the previous edition no longer got right. Many, many hours later, I think I’ve managed to climb back on the tiger.

The most obvious, and therefore least interesting, feature of the new 8th edition is that it catches up with some major developments over the last year, including Carpenter, Wayfair, the GDPR, and the repeal of the network neutrality rules. In some cases, these induced substantial knock-on changes: half of my old network neutrality chapter became obsolete overnight. There are also a lot of smaller updates as newer cases and questions replaced older ones that had fallen behind the times.

In the middle of the scale, I reworked substantial swaths of the jurisdiction and free speech chapters. The jurisdiction chapter now hits unconventional but illuminating topics like choice of law and the scope of Congress’s Commerce Clause authority online. And the speech chapter now deals with much more of the troll playbook, including stalking and impersonation. I also added a section on copyrightability to the copyright chapter, with my usual irascible thoughts on the subject.

And most excitingly, I realized that Internet law has increasingly become the study of what happens on and around platforms, and rebuilt what had been the “private power” chapter around that theme. That led me to craft a new pair of sections: one on how governments can use platforms as chokepoints, and the other on platforms’ rights against governments and users. They lead naturally into the antitrust and network neutrality sections. That chapter finally makes sense, I think.

As usual, there are small corrections and typographical tweaks throughout, plus jokes, snark, and obscure cultural references. I thoroughly enjoyed working on this revision, even as it dragged on and on. I hope that you enjoy reading it, but that it won’t drag for even minute.

As usual, the book is available as a DRM-free PDF download on a pay-what-you-want basis with a suggested price of $30. It’s also available in a perfect-bound paperback version from Amazon for $65.25. Thanks as always to my editors at Semaphore Press for their fairer business model. In true Internet style, we cut out the middleman and pass the savings on to you.

Speech In, Speech Out

I have just posted Speech In, Speech Out, one of several scholarly responses included as part of Ronald K.L. Collins and David M. Skover’s new book, Robotica. The book is their take on how the First Amendment will adapt to an age of robots. To quote from the publisher’s description:

In every era of communications technology – whether print, radio, television, or Internet – some form of government censorship follows to regulate the medium and its messages. Today we are seeing the phenomenon of ‘machine speech’ enhanced by the development of sophisticated artificial intelligence. Ronald K. L. Collins and David M. Skover argue that the First Amendment must provide defenses and justifications for covering and protecting robotic expression. It is irrelevant that a robot is not human and cannot have intentions; what matters is that a human experiences robotic speech as meaningful. This is the constitutional recognition of ‘intentionless free speech’ at the interface of the robot and receiver. …

And here is the abstract to my response in Speech In, Speech Out:

Collins and Skover make a two-step argument about “whether and why First Amendment coverage given to traditional forms of speech should be extended to the data processed and transmitted by robots.” First, they assert (based on reader-response literary criticism) that free speech theory can be “intentionless”: what matters is a listener’s experience of meaning rather than a speaker’s intentions. Second, they conclude that therefore utility will become the new First Amendment norm.

The premise is right, but the conclusion does not follow. Sometimes robotic transmissions are speech and sometimes they aren’t, so the proper question is not “whether and why?” but “when?” Collins and Skover are right that listeners’ experiences can substitute for speakers’ intentions, and in a technological age this will often be a more principled basis for grounding speech claims. But robotic “speech” can be useful for reasons that are not closely linked to listeners’ experiences, and in these cases their proposed “norm of utility” is not really a free speech norm.

Robotica also includes Collins and Skover’s reply to the commenters. In the portion of their reply that discusses Speech In, Speech Out, Collins and Skover say that I have misunderstood their argument by conflating First Amendment coverage (what qualifies as “speech”) and First Amendment protection (what “speech” the government must allow). Intentionless free speech (IFS), discussed in Part II, is a coverage test. Only once it is resolved does the norm of utility, discussed in Part III, take the stage to answer protection questions. Their example about a “robotrader” whose algorithmic buy and sell orders qualify as covered speech comes near the end of Part II, so when I use it to criticize the norm of utility, I am mixing up two distinct pieces of their argument.

This reply is clarifying, though probably not in the way that they intend. They are right that I misunderstood the structure of their argument. But in my defense, Collins and Skover misunderstand it too.

Speech In, Speech Out applies the norm of utility to coverage questions because that is how Robotica applies it. For the robotrader’s messages to other robots to qualify as covered speech, one needs a theory that is not just intentionless but also to some extent receiverless. Collins and Skover claim that there is covered speech when robots exchange information “at the behest of and in the service of human objectives.” (46) But this is an appeal to the purpose and value of the message, not its meaning. If there is a nexus to the reception of speech by a human listener here, it is coming from the norm of utility, not IFS. So if my response anachronistically smuggles Part III’s discussion of protection and the norm of utility back into Part II’s discussion of coverage and IFS, I am only following their lead. The “[c]onfusion over this dichotomy” (113) they perceive in my response is just a look in the mirror.

Although I stand by the criticisms in Speech In, Speech Out, I regret the process that produced it. The principal reason that Collins and Skover and I have spent so long stumbling around in this scholarly hall of mirrors is that our exchange has taken place entirely through completed manuscripts: they wrote their book, we commenters wrote our responses, they wrote their reply. Questions for each other were off the table. They picked the format to promote “[d]ialogic engagement” (111), and there is indeed more dialogue here than in a standard monograph. But compared with the lively, back-and-forth, interactive qualities of a good workshop, conversation, email chain, or even blog-comment thread, one and a half rounds of manuscript exchange aren’t much at all. Fixed-for-all-time publications are a good way to memorialize one’s best understanding of a subject, but there are better ways to converge more quickly on mutual understanding in the first place. In the future, I will look more skeptically on invitations to take part in scholarly projects where ex parte contacts are off-limits.

The Platform is the Message

I’ve posted a new essay, The Platform is the Message, although “rant” might be a better term. At the very least, it fits into the less formal side of my academic writing, as seen in previous essays like Big Data’s Other Privacy Problem. I presented it at the Governance and Regulation of Internet Platforms conference at Georgetown on Friday, and the final version will appear in the Georgetown Law Technology Review as part of a symposium issue from the conference. I’ve been told that my slide deck, which starts with a Tide Pod and ends with the Hindenburg, is unusually dark, even for an event at which panelists were on the whole depressed about the state of the Internet today.

Here’s the abstract:

Facebook and YouTube have promised to take down Tide Pod Challenge videos. Easier said than done. For one thing, on the Internet, the line between advocacy and parody is undefined. Every meme, gif, and video is a bit of both. For another, these platforms are structurally at war with themselves. The same characteristics that make outrageous and offensive content unacceptable are what make it go viral in the first place.

The arc of the Tide Pod Challenge from The Onion to Not The Onion is a microcosm of our modern mediascape. It illustrates how ideas spread and mutate, how they take over platforms and jump between them, and how they resist attempts to stamp them out. It shows why responsible content moderation is necessary, and why responsible content moderation is impossibly hard. And it opens a window on the disturbing demand-driven dynamics of the Internet today, where any desire no matter how perverse or inarticulate can be catered to by the invisible hand of an algorithmic media ecosystem that has no conscious idea what it is doing. Tide Pods are just the tip of the iceberg.

I have very limited ability to make revisions, but I would still be happy to hear your comments and suggestions. I’m still working through my thoughts on these topics, so even if I can’t incorporate much more into this essay, I hope to revisit the issues in the near future.

UPDATE July 29, 2018 : I have posted the final published version; the link is unchanged.

Microsoft and the Government are Both Wrong

I’m taking part in a blog symposium at Just Security on the United States v. Microsoft case currently before the Supreme Court. My essay, thrillingly titled “The Parties in U.S. v. Microsoft Are Misinterpreting the Stored Communications Act’s Warrant Authority” makes two arguments. First, framing the case as a question of whether the SCA is “domestic” or “extraterritorial” is somewhere between misleading and just plain wrong. And second, the SCA should be interpreted as mildly extending the warrant authority in Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41 rather than creating a new warrant authority out of thin air. Both of these points are directed towards the same goal: returning the case to a narrow and tractable question of statutory interpretation rather than a high-stakes clash of grand theories. Here are a few excerpts:

The first problem with this framing is that the Supreme Court’s distinction between domestic and extraterritorial laws is an impediment to understanding. The terms are just empty labels for the conclusion that particular conduct either had or lacked the appropriate connections to the United States. Territoriality arguments may be well-intentioned, but they have the effect of shutting down reasoned analysis by drowning out attempts to determine what the relevant connections actually are. In Internet cases, people with ties to different jurisdictions affect each other in complicated ways: reducing a complex spectrum of cases to a single factor like the location of one party or the location of a server is a recipe for disaster. When I realized that the Supreme Court had granted certiorari in an electronic evidence case that turned on extraterritoriality, I buried my head in my hands.

Congress did not write on a blank slate to create a new kind of “warrant.” Acting as though it did is why Microsoft and the DOJ can give such radically different interpretations of what a “section 2703 warrant” entails. If all you have to go on is traditional warrant practice and Rule 41 is just an example of one kind of warrant, then the problem is open-ended, it is possible to see almost anything in the inkblot, and one is naturally tempted to lean on conclusory canons like the broad-brush presumption against extraterritoriality. But if one reads section 2703(a) as written — incorporating Rule 41 and state warrant procedures except insofar as it allows any “court of competent jurisdiction” to issue one — then one faces a more straightforward problem of statutory interpretation.

Scholars, Teachers, and Servants

I have just posted a short essay, Scholars, Teachers, and Servants, which sets out my views on the essence of a professor’s job. The heart of an academic’s duty is research in the pursuit of truth; scholarship, teaching, and service are three different but mutually supporting uses of the fruits of research. I also say a bit about intellectual corruption, academic freedom, tenure, free speech, and some of the special characteristics of legal academia.